Attack at Derryard: The IRA’s Final Frontal Assault

Inside the 1989 commando-style IRA raid that stunned the British military.

On Wednesday, 13 December 1989, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) conducted an unprecedented, highly organised and lethal frontal assault on a British Army vehicle checkpoint at Derryard, near Rosslea, County Fermanagh. The attack, which resulted in the deaths of two British soldiers and injuries to several others, represented one of the most sophisticated guerrilla operations of the conflict in the North of Ireland, commonly referred to as ‘The Troubles’.

The Derryard Permanent Vehicle Checkpoint (PVCP) was one of 27 fixed military installations positioned near the border with the Southern free state, part of a broader British strategy designed to collect intelligence on the local population and to monitor and restrict the movement of the IRA operating across the frontier. Other installations included hill-top observation posts and fortified patrol bases and fortified vehicle checkpoints. The attack on the Derryard checkpoint demonstrated both the operational capabilities of the IRA’s active service units and the persistent vulnerability of British security infrastructure in rural and border regions, despite efforts at fortification and surveillance.

Beyond its immediate tactical significance, the Derryard attack held wider implications for the political and security landscape in Britain and the Northern state. It served as a striking example of the Provisional IRA’s ongoing adaptation to changing circumstances on the ground and highlighted the limitations of conventional military counterinsurgency approaches in an asymmetric conflict.

The assault on Derryard checkpoint was to be the final commando-style raid executed by the IRA. Furthermore, British casualties decreased every year between 1989 and the 1994 ceasefire.

Historical, Political & Military Context

The attack on the Derryard checkpoint occurred during a period of sustained violence and political deadlock in the North of Ireland. By late 1989, the war commonly known as The Troubles had been ongoing for over two decades, characterised by political stalemate and an entrenched cycle of insurgency and counterinsurgency involving the IRA and other Irish republican groups, the British state and state-sponsored paramilitary organisations, and local security forces.

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), formed in 1969 after a split in the original republican movement, had waged a protracted armed campaign aimed at ending British sovereignty in the North and securing the reunification of Ireland. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the IRA employed a combination of guerrilla tactics, including bombings, assassinations, and ambushes, both in the Northern state and across Britain. By the late 1980s, the organisation had developed increasingly sophisticated operational methods, partly due to enhanced training, the steady influx of modern weaponry, and the organisational shift toward smaller, tightly coordinated Active Service Units (ASUs).

The British government, for its part, had responded with a combination of military enforcement, intelligence operations, and political strategies aimed at containing the insurgency. This approach involved the deployment of regular British Army units, the locally recruited Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), and specialized intelligence branches such as the Force Research Unit (FRU) and the Special Air Service (SAS). Alongside these official structures, a more covert element of British counterinsurgency emerged, involving collusion between elements of the security forces and loyalist paramilitary organisations. A range of inquiries and journalistic investigations have since documented instances where British intelligence agencies either facilitated, directed, or failed to prevent operations carried out by loyalist groups, which targeted republican activists and Catholic civilians alike.

These overlapping methods were supported by an extensive network of fortified security installations along the border between the North and the South.

The British government, intensifying its efforts to fortify the border, demolished bridges and erected concrete barriers, watchtowers, and checkpoints—quite literally cementing the partition between north and south. These measures aimed to suppress the rising support for the Republican Movement and to sever ties between nationalist communities on either side of the divide.

Border regions like South Armagh and Fermanagh became saturated with British military installations, including surveillance towers, patrol bases, and listening posts. This militarised presence fostered a climate of fear and deepened tension within local nationalist communities.

These structures soon became the focus of frequent protests by local residents.

Checkpoints such as Derryard formed a central component of the British strategy, designed both to monitor and restrict cross-border movements and to project British state authority in contested rural areas. Soldiers deployed at these checkpoints sometimes stopped hundreds of vehicles per day, feeding information into a vast intelligence database via two systems: “Vengeful” for vehicles and “Crucible” for individuals. Both fed into the wider intelligence apparatus of the British state, including MI5, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and the military’s own intelligence branches — structures that, in certain instances, were linked to state-sponsored targeted killings.

However, by the end of the 1980s, these static positions increasingly came under criticism from both military analysts and local communities, who viewed them as both militarily vulnerable and politically provocative. The attack on Derryard would dramatically underscore these concerns, illustrating the growing ability of the IRA to challenge the British Army not only through sporadic attacks but through planned, militarily precise engagements against fortified positions.

The Derryard attack thus took place against a backdrop of strategic recalibration on both sides of the conflict. The British government remained committed to a policy of security normalisation and political negotiation, while the IRA leadership, under the dual guidance of its Army Council and Sinn Féin’s political strategists, sought to maintain military pressure in tandem with growing political engagement. The Derryard attack would prove to be both a symbol of the IRA’s operational evolution and a catalyst for renewed debate over the effectiveness of British security policy in the Northern six counties of Ireland.

Fermanagh: IRA Heartland

County Fermanagh remains deeply rooted in Irish republican tradition — a political culture that contributed to the election of IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands as Member of Parliament for Fermanagh and South Tyrone in 1981. Set against the backdrop of centuries of republican sentiment and the systemic discrimination faced by Catholics across both the county and the wider Northern state, Fermanagh was widely regarded as ‘IRA country.’ The area witnessed a sustained campaign in which numerous Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) members and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) reservists were targeted and killed.

Active Service Units (ASUs) were central to most IRA operations — small, highly mobile teams of well-trained guerrillas tasked with carrying out specific, high-impact missions. The cellular reorganisation of the IRA — prompted by the perceived lack of structure in its traditional company and battalion organisation, as well as its vulnerability to informers — was reportedly conceptualised in Long Kesh during the 1970s. This shift evolved in response to changing military tactics and the need for a more flexible and covert approach to operations. Active Service Units (ASUs) operated with precision, employing intelligence, advanced weaponry, and guerrilla tactics to strike vulnerable targets while minimising risk to the attackers.

Warning of Impending Attack

According to reports from British soldiers stationed in the North prior to the Derryard attack, intelligence had suggested the possibility of an impending IRA ‘Christmas present’ — an operation involving an armoured truck somewhere along the border with the South. In response, armour-piercing ammunition was distributed to at least some British Army installations, including the large base at Bessbrook Mill in County Armagh — more than 72 kilometres from Derryard — where the garrison had reportedly been on high alert in the days leading up to the attack.

This suggests that while British forces had forewarning of an attack, the exact target location remained unknown.

According to the Glasgow Herald (later The Herald), in an article published after the Derryard assault, a suspected IRA leader was stopped at a routine vehicle checkpoint in neighbouring County Tyrone two weeks before the attack and had told a British major: ‘Your gift is overdue, but it'll be coming soon.’

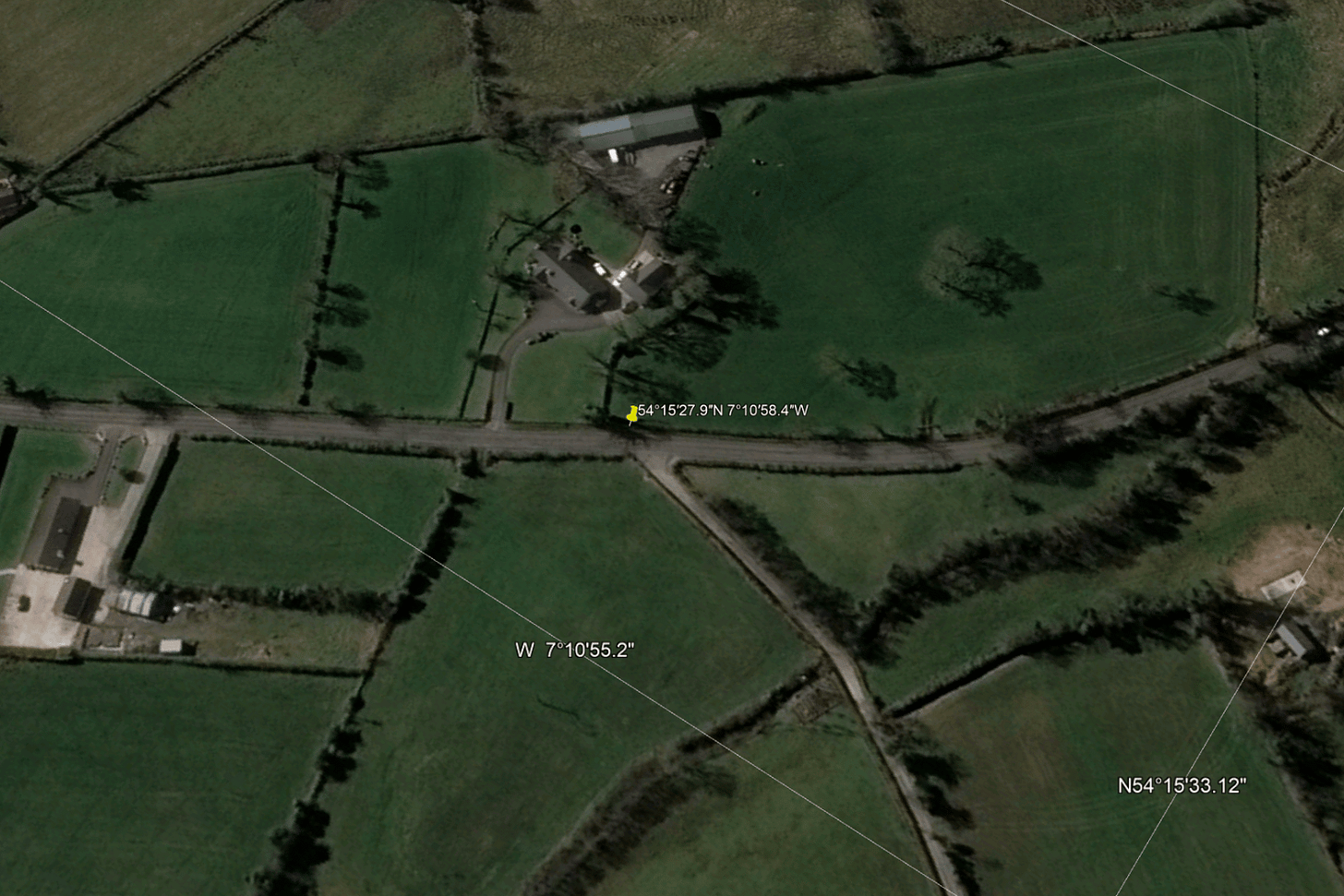

The Derryard Checkpoint

The Derryard Permanent Vehicle Checkpoint (PVCP) was a fortified British Army outpost situated in a remote stretch of rural County Fermanagh, approximately two miles outside the village of Rosslea and just a short distance from the border with County Monaghan in the South. The fortified position was manned by eight soldiers (known as a section and led by a corporal) from the King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB), with a further four soldiers patrolling the vicinity. The position’s geographic isolation, surrounded by dense hedgerows, winding country roads, and scattered farmsteads, made it both a key observation point and a vulnerable target within the British Army’s broader network of border security installations.

Strategically, the checkpoint served as part of the British state’s effort to monitor and control cross-border movement in an area long recognized as a conduit for the Provisional IRA’s logistical operations. The porous nature of the Fermanagh–Monaghan border — much of it made up of “unapproved” roads, narrow lanes, and open countryside — posed a constant challenge for British forces attempting to intercept guerrilla units moving between the North and the South, the latter serving as the logistical bedrock of the IRA.

In all, the British constructed and manned ten fortified checkpoints across the Fermanagh border with the South. Checkpoints such as Derryard were intended to serve both as physical barriers and psychological deterrents, reinforcing the state’s presence in rural areas where the IRA enjoyed strong support — but they also became a constant source of resentment among the local nationalist community, who faced daily harassment and disruption.

Despite its defensive design — which included reinforced sangars, barbed-wire fencing, and a combination of static posts and mobile patrol coverage — the Derryard checkpoint shared many of the structural weaknesses common to border installations during the conflict, such as small, cramped and weak portacabins that offered little protection to soldiers who slept inside. Its isolated position limited the speed at which reinforcements could arrive in the event of an attack, while its fixed nature and predictable routines left it open to sustained observation and pre-attack surveillance by IRA units familiar with the local terrain.

The vulnerability of British soldiers in remote fixed positions underlined what was described by senior British officers in a 1979 World in Action documentary as a ‘dangerous and unrewarding role’ in the North of Ireland.

At the time of the attack, the checkpoint was manned by soldiers of the British Army’s King’s Own Scottish Borderers regiment, alongside personnel from the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) — the latter perceived by the nationalist community as a paramilitary organisation in uniform. The soldiers stationed at Derryard typically conducted vehicle searches, monitored traffic flows, and maintained a visible military presence along the nearby roads — all while adhering to a routine that, though necessary for operational coverage, offered the IRA an opportunity to gather intelligence on shift patterns, defensive procedures, and moments of potential vulnerability.

Coincidentally, just a few days before the attack, newspaper reporters had visited the checkpoint. An article published the day after the attack in the Scottish newspaper The Southern Reporter described the “extremely intense soldiering” experienced by those stationed along the 200-mile border area of the tactical area of responsibility (TAOR):

“The long hours, cramped living conditions and constant pressure of serving in a dangerous and sometimes threatening area would be a heavy load for most young men to face.

Being our here is bound to breed frustration at times, the ‘Jocks’ are living on top of one another and have little privacy.”

At Derryard, the garrison’s day-to-day duties involved long hours of static observation punctuated by random searches and occasional joint patrols with other security forces. For many soldiers, particularly those deployed from Britain, the experience of rural border duty was characterised by a heightened sense of isolation and an awareness that they were operating in an area where the local population often viewed them with suspicion, hostility, or silence.

The IRA’s Shelved “Tet Offensive” Strategy

In the late 1980s, elements within the Provisional IRA leadership reportedly developed a long-term operational strategy informally referred to — both by some members and by British intelligence — as a “Tet-style offensive.” The reference was to the 1968 Tet Offensive launched by the National Liberation Front (NLF) and the North Vietnamese Army against U.S. and allied South Vietnamese forces during the Vietnam War: a highly coordinated wave of simultaneous attacks across dozens of locations that aimed to shock public opinion and demonstrate the insurgents' reach and resilience.

In the IRA’s case, the concept wasn’t intended to mirror the scale of Tet in terms of sheer numbers, but rather for its psychological and political impact: a high-profile surge of spectacular, coordinated, and militarily sophisticated attacks designed to undermine British claims of control, sap morale, and force political movement, particularly at a time when back-channel discussions on a political settlement were tentatively emerging.

The Derryard attack in December 1989 can be understood as an early manifestation of this strategic thinking. It combined many of the hallmarks of what such an “offensive” would require:

— Highly coordinated planning involving volunteers from multiple brigades rather than a local ASU.

— The use of heavy weaponry and military-style assault tactics, including machine guns, RPGs, sandbagged vehicles, and a bomb-laden support vehicle.

— A clear intention to inflict maximum damage on both personnel and the structures symbolizing British military control (the fortified border checkpoint).

— An effort to demonstrate operational reach and tactical evolution, reinforcing the IRA’s capacity to match professional military forces, rather than remaining a purely guerrilla or hit-and-run force.

While the full-scale “Tet-style” escalation never truly materialized in the way some IRA planners had envisioned, Derryard marked both a practical example of that ambition and a proof-of-concept for the IRA’s evolving military doctrine. The attack was one of the clearest signals by the IRA in the late 1980s that it was capable of executing complex, multi-phase assaults — and that its operational focus was shifting from small-scale ambushes to strategic, high-profile engagements designed to challenge British military and political resolve.

The Attack

Planning

A senior Irish republican from South Armagh, according to Ed Moloney’s A Secret History of the IRA, “drastically scaled down” the “Tet-style” offensive. However, an experimental and cross-brigade “flying column” was established under the command of veteran operator Michael “Pete” Ryan from the IRA’s East Tyrone Brigade, who was handpicked by a South Armagh Brigade-based commander. The Derryard operation was to be the first and only one planned by the IRA’s Northern Command — plans that were not shared with the approximately twenty participants until just before the plan was put into action.

The aim of the Derryard assault was to completely destroy the British army position and kill soldiers attached to the checkpoint.

For the Derryard operation, intelligence-gathering would have been critical. The IRA would have invested significant time in studying the checkpoint's layout, the daily routines of soldiers stationed there, resupply cadences, and the surrounding terrain. Sources suggest that the attackers had gathered detailed information about the layout of the checkpoint, its defences, and the shift patterns of the British soldiers, allowing them to time their assault when the garrison was most vulnerable. Additionally, IRA surveillance teams may have monitored the checkpoint for days or weeks prior to the attack, ensuring that they could strike at the most opportune moment.

The Assault Team

The raiding assault group was unusually sourced and assembled. Rather than being drawn from a single local Active Service Unit (ASU), it comprised IRA volunteers from several brigades operating across a wide area of the conflict zone — including South Armagh, North Monaghan, Fermanagh, and East Tyrone.

The group was modelled on a "flying column" — a small, independent, and highly mobile unit designed for rapid attacks and quick withdrawals.

The term "flying column" can be traced back to The Art of War (5th century BC), an ancient Chinese military treatise attributed to the strategist Sun Tzu. Flying columns were later famously adopted by the IRA during the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921) for their attacks against British military and police forces.

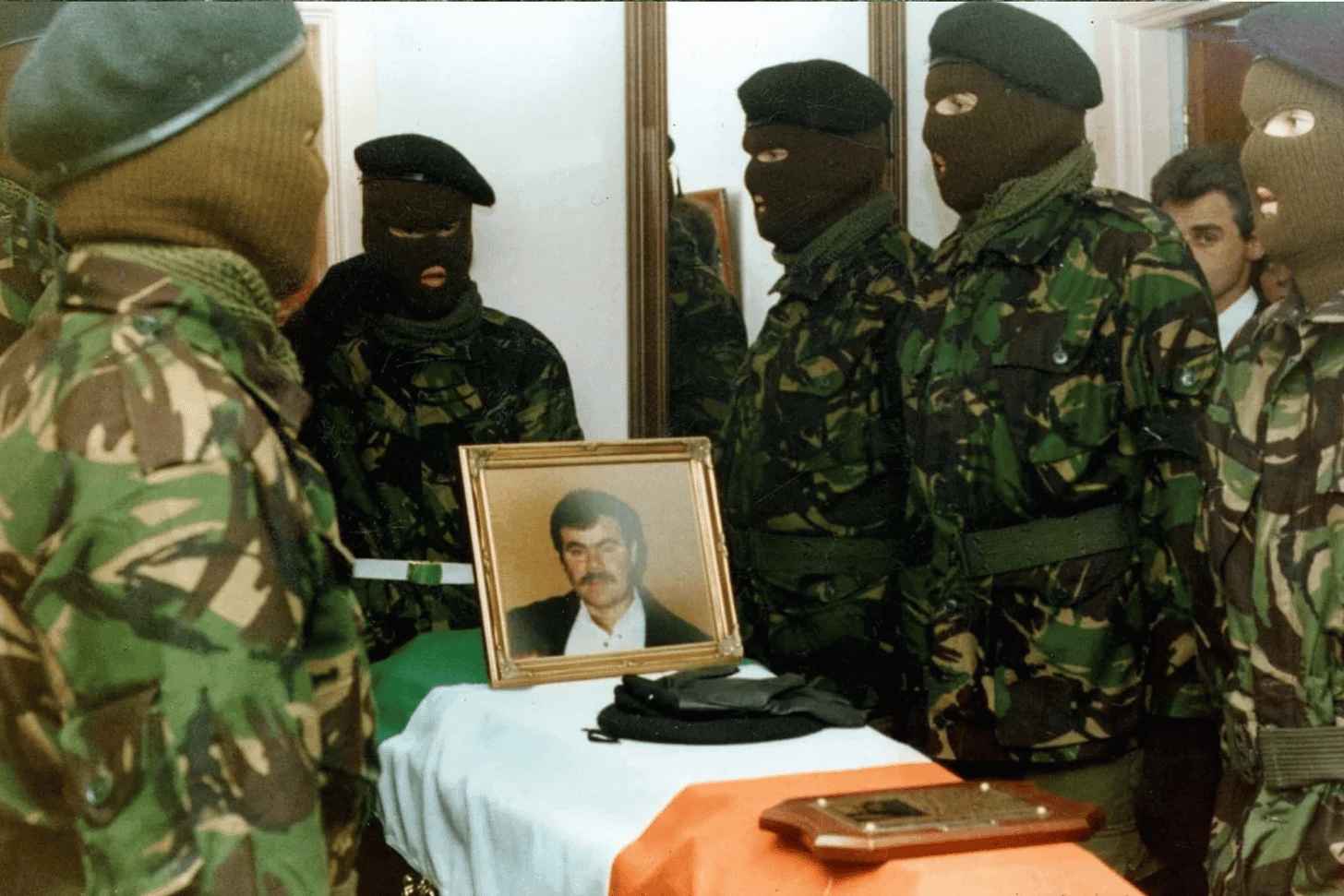

The commanding volunteer, Michael “Pete” Ryan — a 1981 Crumlin Road prison escapee and an individual regarded by British intelligence as “extremely dangerous” — was ambushed and executed by the Special Air Service (SAS) less than two years later, in June 1991.

Contrary to republican sources, The Glasgow Herald (later The Herald) reported that a former British Army NCO from the Parachute Regiment — who later joined the IRA — masterminded the attack and led the assault group. According to “intelligence sources,” the ex-Para was an Irishman who had served in the regiment for several years.

Preparation

Preparations for the engagement began more than a week before the assault, when a Hino quarry lorry was stolen in the South — in Mullingar, County Westmeath — and taken to a farmhouse not far from the Derryard checkpoint.

A purpose-built wooden frame was assembled and placed inside the truck’s loading area, filled with sand, and fitted with three machine gun mounts welded to the edges of the body. The cab was lined with sandbags to shield the driver, and a crash bar was installed on the vehicle’s exterior.

The Assault Begins

On the morning or early afternoon of Wednesday, 13 December 1989, the IRA commandeered a nearby farmhouse with a line-of-sight to the checkpoint — establishing an operational base before the attack commenced.

Shortly before the attack, at around 16:10, IRA volunteers began sealing off roads approaching the Derryard checkpoint installation to prevent civilians from being caught up in the impending assault.

The attack team, numbering at least 20, heavily armed and wearing body armour, had earlier prepared an Isuzu van laden with a 250 kg bomb.

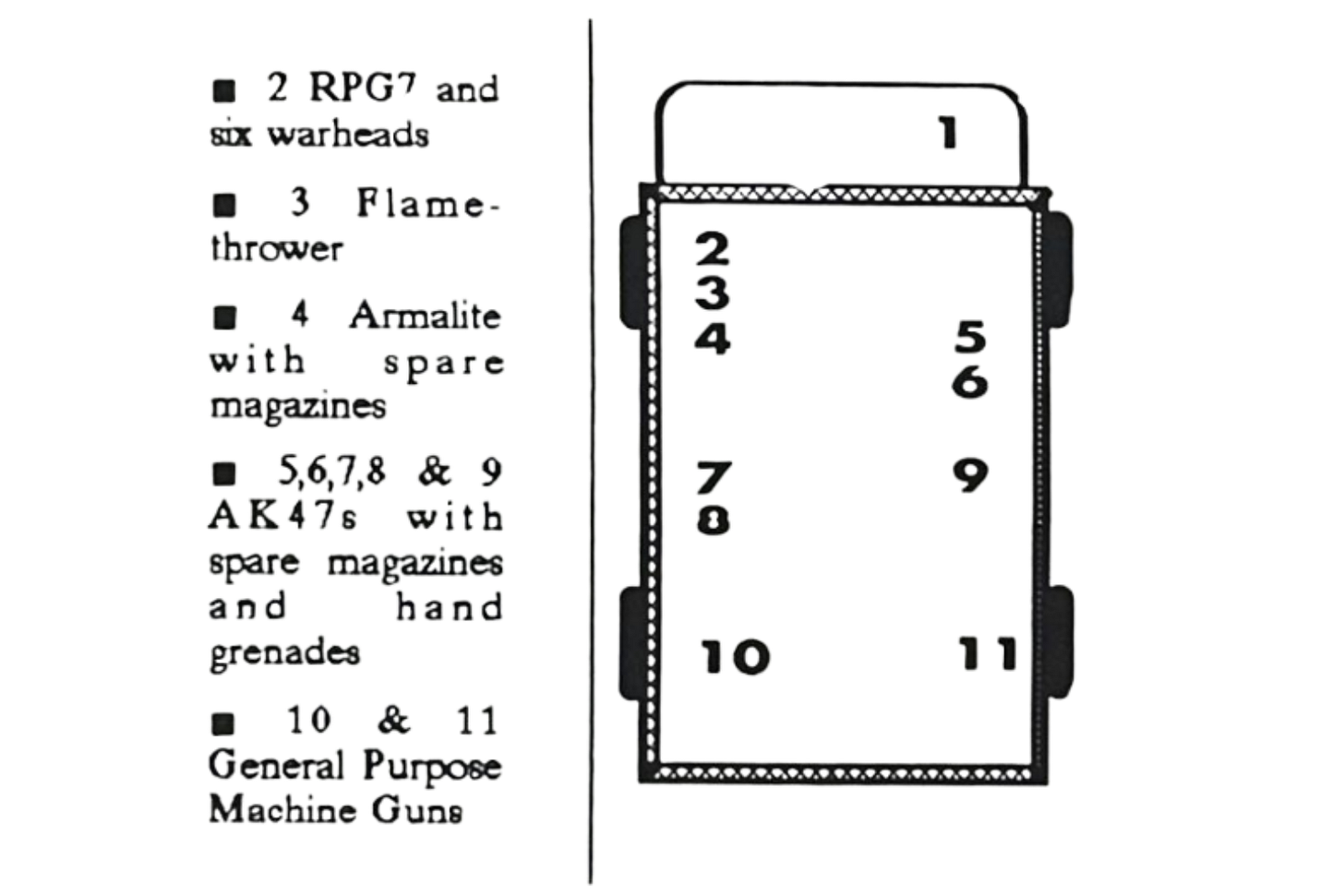

Eleven IRA volunteers — around half the attacking force — arrived at the Derryard checkpoint at approximately 16:20 camouflaged beneath a large tarpaulin in the back of a Hino lorry.

The use of hijacked vehicles was a hallmark of the IRA’s operational style — allowing them to move covertly, bypass routine security checks, and evade detection until the moment of the strike.

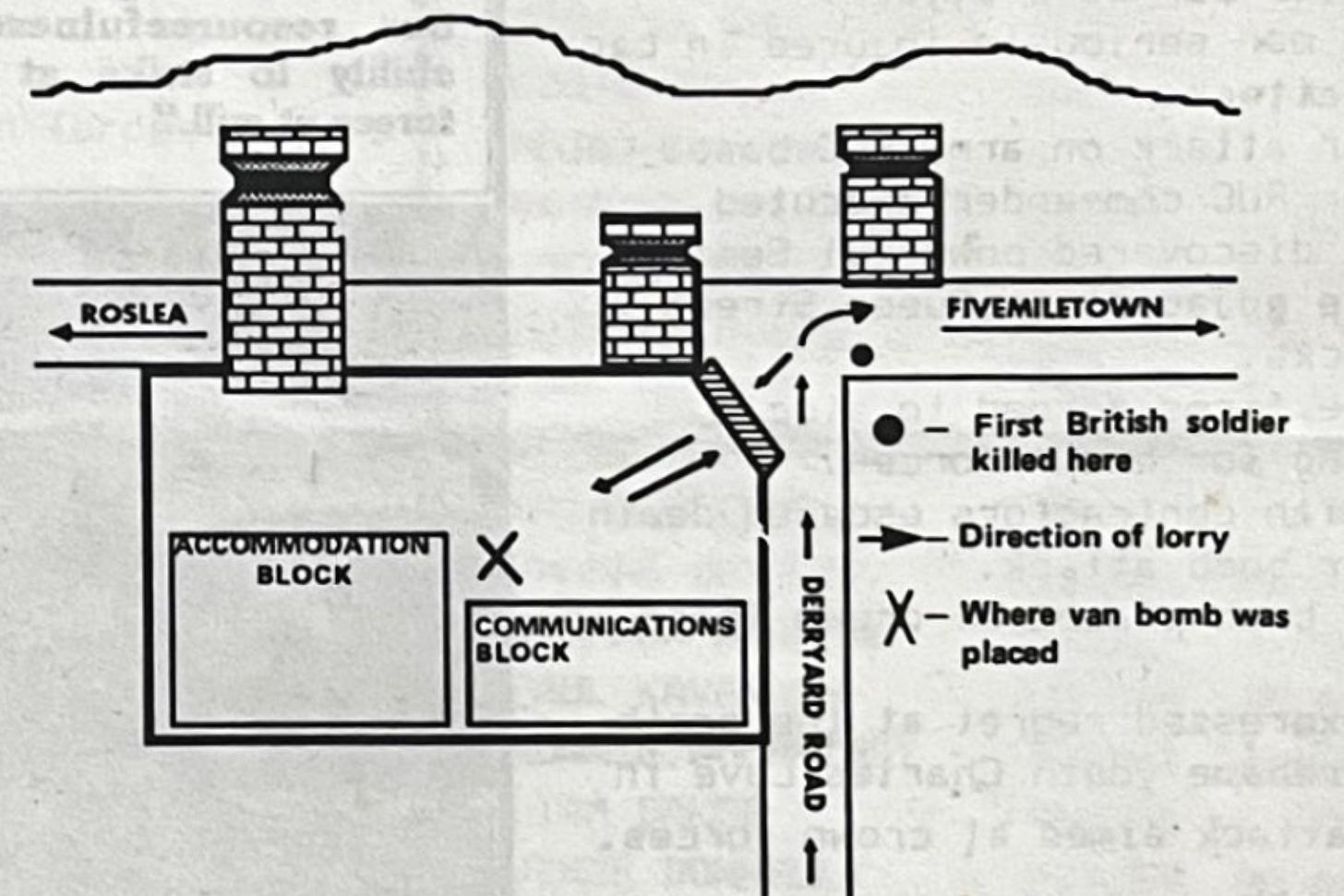

The assault began when the lorry was driven from Derryard Road into the vehicle bay at the centre of the checkpoint, the driver sounded the horn, signalling the volunteers to initiate the attack.

The first British soldier, Private James Houston, was shot dead whilst the rest of the attackers began an attempt to clear the position’s fortifications and compound.

The attack was launched with overwhelming force, employing a combination of heavy weapons intended to maximise damage and ensure success. The volunteers were armed with RPG-7 launchers, an LPO-50 flamethrower, Armalite and AK-47 rifles, two FN MAG general-purpose machine guns (GPMGs), as well as fragmentation grenades and improvised Semtex explosive devices — all used to target both the soldiers and the checkpoint’s defensive infrastructure.

RPGs (Rocket Propelled Grenades) were fired at the largest of the three sentry towers while the machine guns mounted on the sides of the lorry were used to provide heavy covering fire.

Several IRA volunteers dismounted from the high-sided lorry bed and launched attacks on key elements of the checkpoint’s defensive structure. Meanwhile, the attackers operating the GPMGs unleashed a sustained barrage of suppressive fire, to keep British soldiers pinned down and prevent them from mounting an effective response. The sudden and coordinated nature of the assault left the defenders both overwhelmed and disoriented.

The central sentry tower, which guarded the entrance to the compound housing the accommodation and communications block, was then targeted by the attackers using an LPO-50 flamethrower — the first and only time the weapon, supplied through the Libyan arms shipments, was deployed in an IRA attack. A local farmer, quoted in the book Lost Lives, recalled seeing an “orange ball of flame” while gunfire was “raking the fields.”

With the IRA attackers having advanced into the centre of the fortified checkpoint, soldiers stationed in the sentry towers were left firing into their own position.

After rockets were fired at the main sentry post, two of the raiders shifted their focus to the observation tower facing Fivemiletown to the north, where they planted a small but powerful Semtex device.

According to an IRA statement detailing the attack, the next stage of the operation began as volunteers pressed deeper into the walled compound within the checkpoint:

“Volunteer No.1 then ordered a ceasefire and called upon the soldiers to lay down their weapons, if they surrendered to us their lives would be spared.

The IRA cannot take and hold prisoners, but it was our intention to take them with us for some distance and leave them tied up at a prearranged location for them to be later freed. This action would have spoken for itself, that the IRA could be magnanimous towards an enemy who had surrendered and it showed that we were not on this operation only to kill soldiers for the sake of killing them.”

The lorry was then driven out of the checkpoint centre, making space for the deployment of the waiting Isuzu van carrying the 250 kg bomb. It was hoped that this would completely destroy the checkpoint and kill the soldiers taking cover within the compound's structures.

Meanwhile, the IRA’s operator of the Soviet-made flamethrower sprayed flames at the command sangar. According to a report by the King’s Own Scottish Borderers on the attack, the flames were so intense that they “splintered the sangar walls and penetrated inside through the observation ports.”

As the van carrying the bomb entered the compound, three IRA volunteers dismounted and began clearing the portacabin with assault rifles and grenades. Meanwhile, the observation tower facing Roslea started to collapse, with the upper floor caving in. The soldier inside sustained blast burns from at least one RPG strike and the subsequent detonation.

While the van bomb was being primed, a British soldier, Lance-Corporal Michael Patterson, emerged from the compound’s buildings, which were under heavy fire and grenade attack. He refused IRA orders to lay down his weapon and was shot dead.

According to local residents, the attack lasted between fifteen and twenty minutes, marked by intense and sustained gunfire. British soldiers present described it as “terrifying close-quarter action.” Reports suggest that up to 3,000 shots were fired by the IRA during the engagement, in addition to the deployment of the flamethrower—the first and only time the weapon was used in an IRA attack.

British soldiers stationed at a nearby fixed checkpoint in Annaghmartin, about one kilometer away, heard the attack begin and immediately took cover behind the walls of the checkpoint’s compound. They listened to the sustained heavy gunfire and explosions as the IRA advanced on the Derryard checkpoint.

The IRA unit’s use of coordinated crossfire ensured that the British soldiers were caught in a two-pronged assault, limiting their options for counterattack and escape. The IRA targeted key areas of the checkpoint, with RPGs fired at the observation sanger and the flamethrower aimed at the command post. The combination of heavy weaponry, explosives, and tactical coordination created a sudden and overwhelming engagement where the British forces were unable to mount a coordinated defense and were overwhelmed in a matter of minutes.

One half of the Derryard platoon — which had been conducting a foot patrol near the nearby Annaghmartin checkpoint — began making their way back toward the Derryard position upon hearing the attack unfold.

A corporal attached to the British Army foot patrol, taking cover approximately 100 metres from the checkpoint, transmitted a "contact" report via radio — the only communication received by Battalion Headquarters until after the attack had concluded.

The rear of the attackers' lorry was clearly visible to the foot patrol, while the assault team aggressively advanced toward the centre of the position, throwing hand grenades over the walls. As the foot patrol opened fire on the lorry and into their own base, they were quickly met with sustained return fire from the IRA unit, who used the mounted GPMGs as the attackers made their withdrawal.

In addition to the two soldiers who were killed during the attack, several other soldiers were injured, including one who kicked an unexploded grenade away when he was targeted by a second grenade, which caused shrapnel injuries to his back and side. The exact number of casualties remains unknown. The failure of the bomb carried by the Isuzu van to fully detonate (only the device’s ‘booster’ — an intermediate charge — exploded) doubtlessly saved the garrison from further deaths.

Exit and Evasion

Following the successful execution of the attack, the IRA unit exfiltrated the area, one of the raiders seizing a Browning Hi-Power pistol from a dead soldier. The attackers were well-trained in evading capture and had planned their withdrawal route carefully, taking advantage of the surrounding terrain to disappear into the rural landscape. The escape route likely involved a series of pre-arranged contingencies, ensuring that the IRA members could evade British forces despite their immediate response.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack, the British Army launched a rapid response, with a Westland Wessex helicopter ferrying reinforcements to the scene — and later evacuating the dead and wounded. The IRA raiders fired at the helicopter, but at risk of being surrounded, began to withdraw from the area.

The British set about sealing off the area before beginning to evacuate the casualties. Nearby border checkpoints were reinforced, and roadblocks were set up in an attempt to trap the attackers. However, the IRA's knowledge of the terrain and their ability to blend into the local environment meant that, by the time British forces were mobilized, the attackers had already melted away, avoiding capture.

Upon realising that the Isuzu van contained a bomb, the soldiers evacuated the area and established a security cordon around the checkpoint. The hijacked lorry was later discovered abandoned near the border, with a 200 kg explosive device concealed inside.

The aftermath of the attack saw the British military escalate security measures, both in terms of personnel and surveillance, along the border. The Derryard checkpoint, along with others in the region, would be subjected to more stringent defenses in an effort to prevent future attacks. Despite these measures, the Derryard operation demonstrated the vulnerability of British forces even in heavily fortified positions, forcing the military to reassess its strategy for securing the border areas.

Aftermath and Impact

Immediate Aftermath

Following the Derryard checkpoint attack, the British Army launched an immediate response aimed at securing the area and apprehending the attackers. The British military swiftly cordoned off the vicinity of the checkpoint, establishing a security perimeter and setting up roadblocks in an attempt to catch the perpetrators as they withdrew.

This was a routine measure in the aftermath of attacks, designed to contain the situation and prevent any further strikes in the region. In addition to the immediate search operation, the British Army reinforced their military presence in the border region, deploying additional patrols and increasing surveillance in an effort to pre-empt further IRA activity.

The response, however, was hampered by several factors. First, the attackers’ ability to vanish into the surrounding countryside after the assault showcased the effectiveness of IRA tactics and their deep knowledge of the local terrain. The immediate manhunt that followed the attack did not yield the desired results, as the IRA unit, employing expert counter-surveillance tactics, successfully evaded capture.

Second, the attack highlighted a recurring weakness in British military strategy: despite the heavy fortification of checkpoints like Derryard, British forces were vulnerable to well-planned and expertly executed guerrilla attacks. The relatively high number of casualties, including the deaths of two soldiers, was a stark reminder of the risks posed by IRA operations, even in heavily fortified positions.

A senior British officer, quoted in the Glasgow Herald commented: “They are murdering bastards but they are not cowards. This team actually pressed home a ground attack right into the heart of the compound. That takes guts when there are people firing back.”

KOSB officers and security sources believed that the PIRA unit involved was not locally recruited, rather executed by IRA members from Clogher (County Tyrone) and Monaghan across the border. The same sources said that the plan of the attack was executed "in true backside-or-bust Para style".

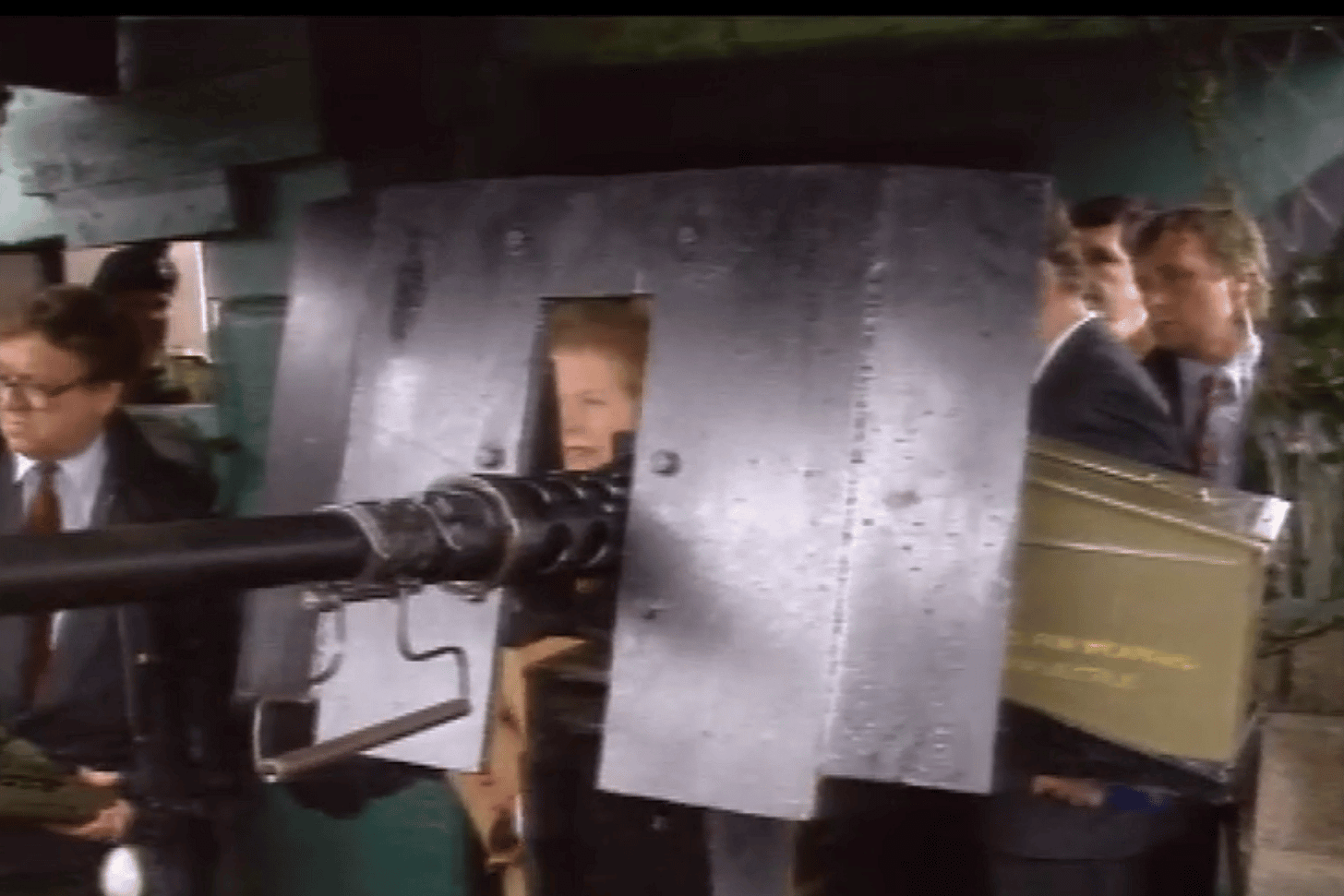

Within days, a British army team moved in to reinstall CCTV and communications equipment and more notably — the position, along with dozens of other British military checkpoints throughout the North of Ireland, was equipped with a .50 calibre Browning machine gun.

A former British Commanding Officer from the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, reflecting on the Derryard attack in a statement published in the regiment’s magazine on the 30th anniversary in 2019, wrote about the shock of arriving on the scene:

"No one had the faintest clue about the scale of the attack the IRA had put together.

Yes, we knew about the Libyan weapons, but to this day no one has ever confirmed to me that there was any inkling within intelligence circles that the IRA would use the full range of weaponry and explosives in such a way.

At that time of year, daylight faded quickly. The IRA attacked Derryard at approximately 16:20 hours and, as we discovered, it was almost pitch black by 17:00 hours.

Then, of course, the first contact report came into Main Operations.

As a lot of us know from endless training and then endless tours — when there is a ‘contact’, a number of response systems at different levels need to and have to snap into action instantly, and these actions have to be correct. If anything could stretch these responses and procedures to breaking point, then Derryard was it.

I would be lying if I said I could remember exactly what happened, but these are my recollections:

I had a brilliant Main Headquarters team. The Adjutant called me into the Operations Room and, with the Operations Officer, we quickly talked everything through.

All the functions had kicked into gear, and my overriding need was to get out to Derryard.

X and Y had scrambled the Quick Reaction Force and were handling the operational needs — both upwards to Headquarters 3 Brigade and downwards to the companies and other static call signs. G would provide the top cover and guidance once I had left.

B and the Intelligence Cell were tapping into all the Royal Ulster Constabulary and Special Branch channels to try and get an understanding of what had and was happening.

The Regimental Signals Officer and all the signalers were keeping everything connected.

Meanwhile, C and the clerical team under D were making sure everything was being recorded and were liaising closely with Echelon at St. Angelo.

E and his small medical team were standing by. They knew they were in for a tough time.

I had to get to Derryard, but the priority for the Lynxes was to get more Jocks into the area and to get the casualties out.

I remember my awful feelings of anger and hurt as the casualties and some of the survivors were helped off the first helicopter back from Derryard and taken into the tender care of the medics, from where they were later airlifted to Musgrave Park Hospital.

I will keep those sights and thoughts to myself because they were terrible.

It was obvious Roslea was the focus, so X drove the two of us there in our covert car, from where we joined the next reinforcements and lifted off.

Then we landed just outside the base at Derryard and, as I moved towards the PVCP, my heart almost stopped.

The base was wrecked and smouldering in the frosty darkening light.

One thing that struck me in the SIB’s account was when they wrote:

‘For the terrorists, it was a soft target: being tactically indefensible, poorly protected, and manned with a minimum of weaponry.’

The Army's failure to equip, man, and protect an isolated position is something that would be repeated in numerous FOBs (Forward Operating Bases) in Afghanistan 20 years later."

The soldiers at Derryard were ill-equipped to defend against such a determined and well-armed enemy. Heavy support weapons like mortars and artillery were deemed unsuitable for British COIN (counterinsurgency) operations in the North of Ireland, and Permanent Vehicle Checkpoints (PVCPs) were rarely fitted with GPMGs at the time. In response, the British military issued an Urgent Operational Requirement for a rifle grenade capable of repelling similar attacks. The solution was ultimately sourced from the French company Luchaire — resulting in the L74A1, a lightweight, armour-piercing grenade designed to counter the light vehicles increasingly used by the IRA.

Long-Term Impact

In the broader context of the conflict, the attack on the Derryard checkpoint had profound consequences for both the British military and the IRA. For the British Army, it reinforced the strategic difficulties they faced in securing the border areas. The attack underscored the vulnerability of fixed military positions, especially when faced with the IRA’s growing expertise in guerrilla warfare and the use of heavy weaponry.

In response, the British military increased fortifications and stepped up efforts to counter IRA intelligence operations. There was a noticeable shift in the deployment of British forces in the North of Ireland, with more attention given to intelligence gathering, surveillance, and covert operations aimed at infiltrating IRA cells. Checkpoints like Derryard, once seen as passive defensive positions, became more heavily militarised, though this also led to greater tension with local communities, particularly in nationalist areas where the British military’s presence was viewed as an occupying force.

For the IRA, the Derryard attack represented another successful operation in their ongoing campaign against British forces in the Northern state. The attack demonstrated the capability of IRA Active Service Units (ASUs) to carry out complex, coordinated assaults with precision. The use of heavy weapons such as RPG-7s, FN MAG machine guns, and AK-47s, along with the well-planned ambush, further cemented the IRA's reputation as a formidable military force capable of striking at the heart of the British security apparatus.

The success of this operation, along with others during this period, provided a significant boost to morale within the IRA and its supporters. It reinforced the perception that the organisation was capable of taking the fight to the British military, despite the immense power disparity between the two forces. The Derryard checkpoint attack was part of a broader trend in IRA operations at the time, which sought to keep the British military in a constant state of alert, forcing them to divert resources into the border regions and other contested areas.

Political and Psychological Impact

Beyond the tactical and military consequences, the attack on Derryard also had a psychological impact. The IRA’s ability to successfully target a well-defended British Army position sent a clear message to both the local population and the international community: the IRA remained a potent force capable of striking where it mattered most.

In the political sphere, the attack added to the mounting pressure on the British government to address the ongoing conflict in Ireland. The conflict had entered its second decade, and attacks like the one at Derryard highlighted the enduring strength of the republican insurgency. Internationally, the incident further complicated British efforts to maintain the narrative that their security presence in Ireland was necessary for peace and stability. As the conflict dragged on, the legitimacy of the British position began to come under increasing scrutiny, both within Ireland and abroad.

For the Irish nationalist community, the attack served as a symbol of resistance against British rule, with many viewing the IRA as a necessary force fighting for the protection of their rights and their land. However, for the Unionist population and those loyal to the British government, the attack deepened the belief that the IRA posed a direct threat to their security, leading to an intensification of counterinsurgency efforts and a hardening of attitudes towards nationalist demands for Irish reunification.

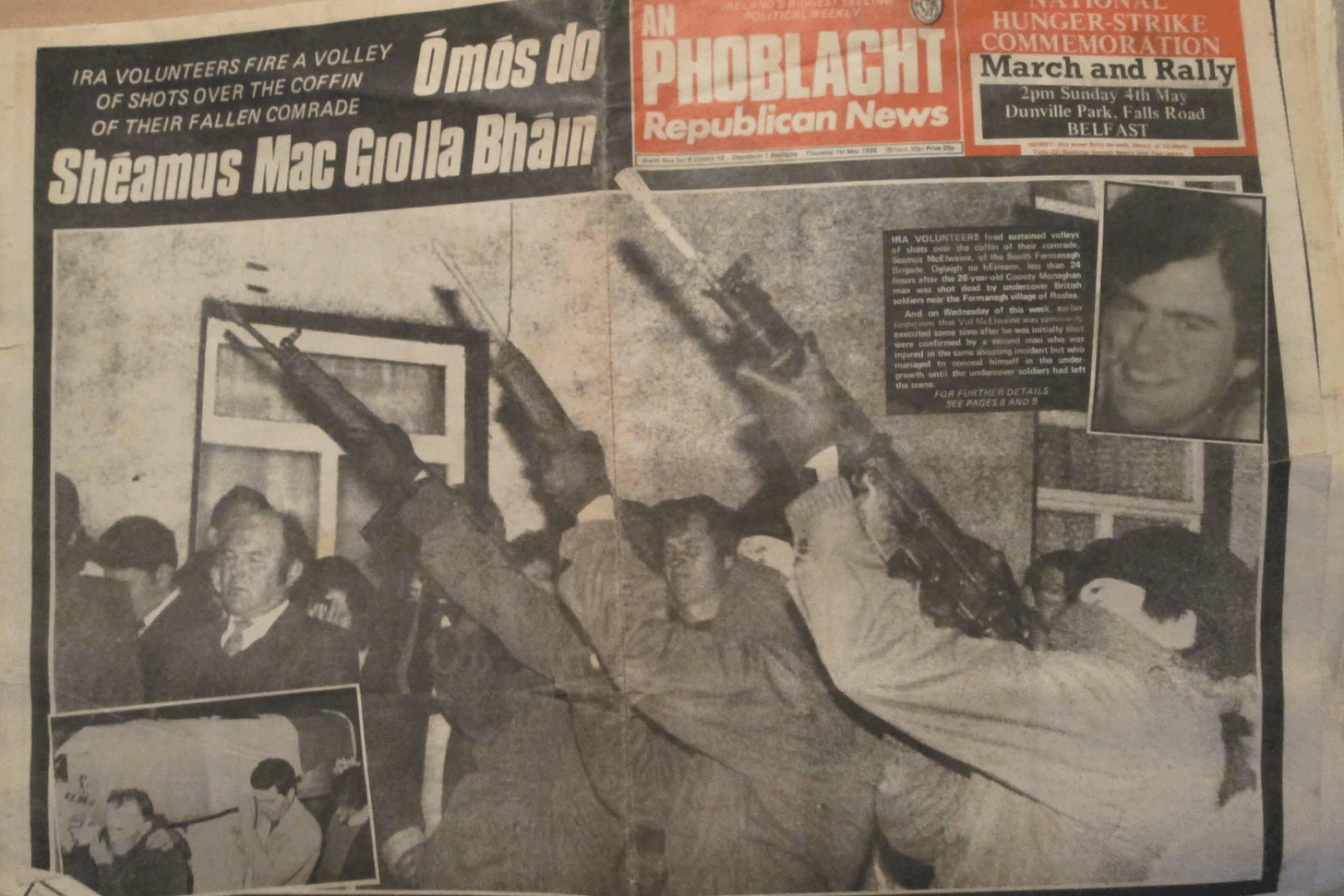

In Irish Republican Folklore

The attack on the Derryard checkpoint was celebrated in the Republican Movement’s weekly An Phoblacht newspaper, as well as in other associated Irish Republican publications at the time. It was framed as a bold and highly successful act of resistance against British military occupation, highlighting the Provisional IRA’s operational capabilities and resolve.

A song was later written and recorded by republican artist Gerry Cunningham:

Throughout this many years of war, many gallant deeds were done

By brave young men of Irish stock with rifle and with gun.

They fought those British forces in the name of the I.R.A.,

And none was more successful than the one so near Roslea.

It was on a Tuesday evening, and the mist was coming down,

When Sky turned to Rodney, and said ‘I think I hear a soond’,

But as they left that lookout post, they raced back in a hurry,

Said “Hoots man don’t go out there, for the Provos are in the lorry!"

So come on boys up the Provos, let's hear your voices cheer —

We'll talk about this victory for many and many a year.

And in the years that have to come, we’ll look back upon this day,

On the attack on Derryard lookout post near the village of Roslea.

When the battle raged on furiously and what a noise did make,

With bullets and with rifles, with guns and hand grenades —

"I think I better get oot of here, for I think I'll breathe my last,

For the Provos have a flame-thrower, they're going to burn me bloody arse!

"Oh we'll send reinforcements!" the policemen quickly said,

"For the Provos have overrun us, and soon we'll all be dead."

And taking down his trusty pack, took out his telephone,

When the answer came back quickly: Tough luck, you’re on your own!

So come on boys up the Provos, let's hear your voices cheer —

We'll talk about this victory for many and many a year.

And in the years that have to come, we’ll look back upon this day,

On the attack on Derryard lookout post near the village of Roslea.

Now the politicians were outraged by this audacious crime,

I think Libya is behind it this time," when up pops Ian Paisley:

"Prime Minister, I assure you, for, according to UDR intelligence,

Colonel Gaddafi was driving the lorry!"

"Oh no," says Ken McGuiness — I think I know them all,

For I have their photographs upon my bedroom wall.

And if you want a poppy, you'd better be discreet,

For you don't have to go to the toilet here to have the security leak!"

So come on boys up the Provos, let's hear your voices cheer —

We'll talk about this victory for many and many a year.

And in the years that have to come, we’ll look back upon this day,

On the attack on Derryard lookout post near the village of Roslea.

So now to finish my story — what happened there that day,

When the volunteers attacked that place near the village of Roslea.

Well done, you gallant soldiers — may you fight another day,

And victory to the volunteers of the Provisional IRA!

So come on boys up the Provos, let's hear your voices cheer —

We'll talk about this victory for many and many a year.

And in the years that have to come, we’ll look back upon this day,

On the attack on Derryard lookout post near the village of Roslea.

On the attack on Derryard lookout post near the village of Roslea.

Conclusion

The attack on the Derryard checkpoint by the Provisional IRA on December 13, 1989, represents a pivotal moment in the broader context of the conflict. Through meticulous planning, precise execution, and a highly coordinated attack, the IRA demonstrated its evolving military capabilities, exploiting the vulnerabilities of a heavily fortified British Army position. The use of heavy weaponry, the element of surprise, and the ability to vanish into the surrounding countryside after the operation highlighted the growing sophistication of the IRA’s tactics during the latter stages of the Troubles.

The immediate aftermath of the attack saw a swift British military response, with reinforced security measures and an intensified focus on intelligence gathering. However, the attackers’ success underscored a deeper, strategic vulnerability in the British military’s approach to securing contested areas. While the British Army sought to tighten control over the border regions, the attack at Derryard emphasized the ongoing risks posed by the IRA’s guerrilla warfare strategy.

Politically and psychologically, the attack reinforced the perception of the IRA as a capable, formidable force, able to strike at the heart of the British presence in the North of Ireland. For the nationalist community, it was a symbol of resistance, while for Unionists, it solidified the view of the IRA as an existential threat. The attack also contributed to the increasing international pressure on the British government, which faced growing calls for a political resolution to the conflict.

In the years following the Derryard attack, the conflict in the North of Ireland would continue, marked by ongoing military confrontations and political deadlock. However, incidents like the assault on the checkpoint marked a shift in the nature of the conflict, demonstrating the IRA’s ability to challenge British authority through targeted, high-profile operations. The legacy of such attacks remains a crucial part of the historical narrative of the conflict in Ireland.

Further Reading & References

An Phoblacht, various issues (December 1989 – January 1990)

The Irish Republican Digital Archive

Ireland’s War Newspaper, Summer 1990

Aaron Edwards, Agents of Influence: Britain’s Secret Intelligence War Against the IRA

Ed Moloney, A Secret History of the IRA

The Glasgow Herald, December 1989

David McKittrick et al., Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children Who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles

British Army Regiment Magazine (King’s Own Scottish Borderers, 2019 Anniversary Issue)