The Ghost of South Armagh

Captain Robert Nairac, Collusion, and Britain’s Secret War in Ireland.

Few figures from the conflict known as “the Troubles” evoke more suspicion, myth, and controversy than Captain Robert Nairac. While officially commemorated as a courageous British Army officer who died gathering intelligence behind enemy lines, he is remembered very differently within the Irish republican community—not merely as a soldier, but as a central figure in Britain’s covert war in Ireland. This was a campaign not fought in open battle, but in shadow: a strategy built on collusion with loyalist paramilitaries, the deployment of assassination squads, and the systematic targeting of civilians.

In nationalist towns and rural parishes across the North, his name is not spoken with reverence, but with accusation. Nairac is remembered not as a shadowy operator, but as a visible and deeply embedded figure—someone who moved openly through loyalist circles, shielded by rank and sanctioned by the state.

On the night of Saturday, 14 May 1977, he was abducted in South Armagh, interrogated, and ultimately executed. His remains have never been found, and he remains one of the most high-profile of the conflict’s “disappeared” — sixteen people who were killed and secretly buried by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA).

Throughout the conflict, growing evidence and testimony pointed to a disturbing pattern: elements within the security forces were not merely failing to prevent loyalist violence—they were enabling it. Intelligence officers and Special Branch agents were accused of protecting loyalist operatives in exchange for information, or worse—actively guiding loyalist groups as proxy forces. These claims included the provision of intelligence on targets, the supply of arms, and logistical support for attacks. At the centre of many such allegations stood the name of Captain Robert Nairac—a man whose reputation became inextricably linked with the blurred and deadly boundary between counterinsurgency and collusion.

Who Was Captain Robert Nairac?

Official accounts have often portrayed Captain Robert Nairac as a rogue operator—an idealistic, over-zealous young officer with a romanticised view of undercover warfare. Yet this characterisation is difficult to reconcile with broader patterns of covert activity during the conflict: the systematic presence of state-linked personnel at scenes of targeted killings, the impunity with which certain operatives moved through loyalist circles, and the persistent shielding of such individuals from prosecution. In Irish republican memory, Nairac was no lone wolf. He was a visible cog in an invisible machine—one that turned quietly behind the official denial of Britain’s “dirty war” in Ireland.

Among soldiers, Nairac’s reputation was anything but typical. When he arrived in Belfast in August 1973 during a handover with a fellow Grenadier Guards officer, he immediately stood out—not for polish or pedigree, but for his stocky build, broken nose, and restless intensity. Described as sharp, curious, and relentless, Nairac was “like a foxhound”—absorbing detail from street patrols around the Shankill and Ardoyne with the obsessive focus of someone intent on mastering a war zone.¹

At a stage in the tour when most officers were cautious and fatigued, Nairac demanded to join the very first patrol available. His zeal signalled something more than mere military curiosity.

That intensity had been honed long before Belfast. Educated at Ampleforth College and later at Lincoln College, Oxford, where he read history, Nairac was known for his eccentric charm, athleticism, and flashes of theatrical flair. He revived the university boxing club and boxed competitively for Gloucester City. After Oxford, he trained at Sandhurst, commissioned into the Grenadier Guards, and was eventually selected for service with 22 SAS. He also received specialist intelligence training at Ashford, Kent, and is believed to have undergone briefing for MI6-related duties in the North of Ireland.

His methods reflected this hybrid preparation. To hone his cover, he reportedly worked casual jobs in Irish neighbourhoods in London to perfect his accent. In Belfast, he was frequently seen socialising with working-class loyalist youth gangs along the city’s peace lines. According to Soldier magazine (March 1979), by 1973 Nairac had embedded himself within the “Local Fianna and Tartan gangs”—inhabiting a liminal role as both military officer and street-level operator.²

His fascination with Irish culture and nationalist songs—often performed during undercover operations—suggested not only strategic mimicry, but a certain theatricality that blurred the line between role and reality. Some who encountered him described a man deeply committed to his mission, yet strangely captivated by the mythology that surrounded it. To others, his behaviour hinted at something more ambiguous: a figure not merely impersonating the conflict, but becoming entangled in its emotional and symbolic currents.

Britain’s Dirty War Begins

The outbreak of widespread civil unrest in 1969, followed by the deployment of British troops, marked the beginning of a new phase in the conflict that would come to be known as the Troubles. From the ashes of that crisis, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) emerged, committed to an armed campaign against British rule in the North. By the early 1970s, this campaign had intensified into a guerrilla war, with bombings, ambushes, and targeted killings becoming regular features of daily life. In response, the British state began to abandon traditional policing and military approaches in favour of more covert, irregular, and extra-legal methods.

One of the architects of this shift was Brigadier Frank Kitson, who arrived to Belfast in 1970 to command the British Army’s 39 Infantry Brigade. A veteran of colonial counterinsurgency operations in Kenya, Malaya, and Oman, Kitson brought with him a strategic framework developed in the context of Britain’s imperial wars. Rather than rely solely on overt military force, Kitson’s approach centred on psychological warfare, deception, and infiltration, often operating outside the bounds of conventional law. He codified these principles in his 1971 manual, Low Intensity Operations, which would become a cornerstone of British counterinsurgency doctrine in the North.

A key element of Kitson’s strategy was the use of pseudo-gangs: armed groups that either mimicked or co-opted local paramilitary actors, enabling the state to penetrate and disrupt insurgent networks from within. These formations, which drew directly on tactics developed in Britain's colonial campaigns, blurred the line between insurgency and counterinsurgency. Operating with varying degrees of official oversight, they were supported by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), MI5, MI6, and specialised units within the British Army.

Alongside pseudo-gangs, other covert techniques were deployed: the recruitment and control of informers; the strategic use of undercover operatives in civilian dress; and the orchestration of false flag operations, designed to discredit republican paramilitaries or provoke sectarian reprisals. These operations were often conducted in ways that preserved plausible deniability for British authorities, allowing the state to manipulate violence while disavowing responsibility. Though the full extent of these activities remains contested, extensive testimony from republican communities, investigative journalists, and whistle-blowers has provided a body of evidence pointing to systemic collusion with loyalist groups and a sustained campaign of covert repression.

The Military Reconnaissance Force (MRF), established in early 1972, became one of the most notorious instruments of this strategy. Comprising undercover soldiers operating in plain clothes, the MRF conducted surveillance, ran agents, and, according to later admissions, engaged in covert armed actions against civilians. MRF operatives were equipped with so-called “Q-cars”—civilian vehicles fitted with hidden surveillance equipment and armour plating. In addition to standard-issue weapons, they carried modified firearms and interchangeable components, designed to hinder forensic identification and frustrate ballistics investigations.

During the 1972 IRA ceasefire, MRF operatives were implicated in a series of shootings targeting civilians. In November of that year, the British Army admitted that the MRF had used unmarked cars to fire on civilians in at least three incidents, one of which occurred on 22 June 1972—the same day the IRA announced its intention to enter a truce.³ The use of IRA-associated weapons in these attacks strongly suggested an attempt to frame republican units, discredit the ceasefire, and trigger retaliatory violence. These tactics—combining manipulation, lethality, and psychological provocation—would later echo in atrocities such as the Miami Showband massacre.

The period also saw early indications of Special Air Service (SAS) involvement in covert operations. Though officially denied at the time, SAS personnel had been active in the North since 1969. By 1972, they were reportedly working in tandem with the MRF in some of the first documented black operations against republican targets. One particularly striking incident came in December 1972, when a former soldier named David Seaman held a press conference in Dublin. Seaman claimed that he had been part of a British military unit—believed to be linked to the SAS—tasked with carrying out bombings designed to discredit the IRA and manipulate political outcomes. His statement appeared to refer directly to operations such as the 1 December 1972 Dublin car bombings, in which two civilians were killed just hours before a vote on a controversial anti-terrorism bill in the Irish Parliament.

Shortly after his public disclosure, Seaman was found shot in the head. His killers were never identified. Although the Irish Justice Minister later denied that an official report had implicated the SAS, suspicions of British military involvement persisted, fuelled by the political timing of the bombings, Seaman’s claims, and the strategic value of shifting blame onto the IRA.

It was within this shifting landscape of unofficial warfare—where legal frameworks were circumvented, and military logic merged with psychological operations—that Captain Robert Nairac began his intelligence career. Although later remembered primarily for his deep-cover activities in South Armagh, his first operational deployment took place in Belfast, one of the conflict’s most contested urban arenas. There, he is believed to have worked alongside emerging military intelligence units, including the MRF and potentially MI5, gaining experience in surveillance, informant handling, and undercover patrols.

These early operations laid the groundwork for Nairac’s later role in the rural South, where the conflict became less visible but no less violent. As the British state moved from policing to psychological and paramilitary-style warfare, figures like Nairac emerged as the embodiment of a strategy that dissolved the boundaries between soldier, spy, and provocateur.

These early urban operations laid the groundwork for Nairac’s eventual deployment to South Armagh—a region where the terrain, politics, and republican tradition presented a uniquely hostile environment for British intelligence.

South Armagh — IRA Heartland

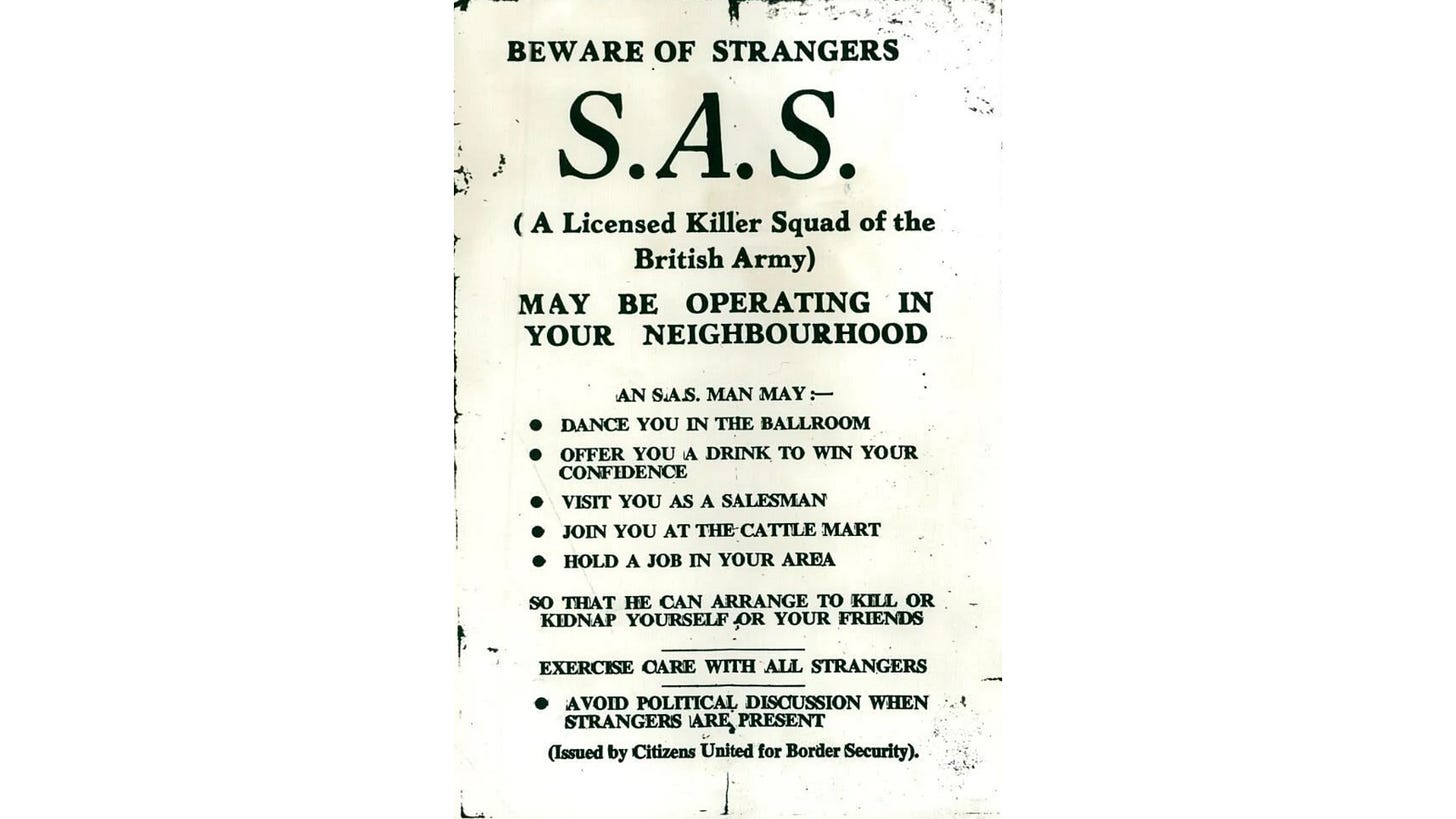

By the mid-1970s, South Armagh had become one of the most militarised and contested regions in the Six Counties of the North of Ireland. Long steeped in Irish nationalist tradition and shaped by centuries of resistance to foreign invasion, the area had earned a reputation as both a stronghold of republican sentiment and a crucible of guerrilla warfare. The landscape—rugged, rural, and bordered by the Republic—was ideally suited to the tactics of the Provisional IRA. Ambushes, sniper attacks, and roadside bombs were routine. British forces, increasingly unable to patrol safely by road, came to rely on helicopter transport and a network of fortified surveillance towers.

Culvert bombs—fertiliser-based devices activated by command wire—were frequently deployed to ambush convoys and assert control over strategic routes. But it was not just the terrain that protected the IRA: the social fabric of South Armagh—tight-knit, insular, and generationally republican—rendered the region uniquely resistant to penetration. Many IRA units were composed of extended family networks, where blood ties and long-standing communal trust severely limited the chances of successful infiltration. Outsiders were quickly recognised, and informers, once discovered, were dealt with swiftly and decisively.

It was into this environment that Captain Robert Nairac was deployed under deep cover. By 1974–75, he had shifted his focus from Belfast to the countryside, operating out of the fortified base at Bessbrook Mill. There, he was part of a broader British counterinsurgency strategy involving elements of the Special Air Service (SAS), 14 Intelligence Company, and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) Special Branch. These units functioned in overlapping and sometimes uncoordinated spheres, creating a complex web of surveillance, infiltration, and covert action.

Nairac’s cover identity was carefully maintained. He operated a civilian vehicle outfitted with surveillance technology: a high-frequency transmitter disguised as a standard car radio, a concealed microphone mounted beneath the seat, and a panic button within reach to silently alert nearby units if his position was compromised. This reflected the broader technical evolution of British intelligence operations in the area—an advancement from the rudimentary tactics associated with the discredited Military Reconnaissance Force (MRF).

But technology was only one element of Nairac’s tradecraft. In Talking to People in South Armagh—a classified internal guide he authored—Nairac laid out a psychological and cultural approach to intelligence gathering. “Just as it is important to regard everyone with serious suspicion,” he wrote, “it is also important to regard any local as a potential source of information.” He estimated that up to 80% of the population were weary of violence and might provide intelligence if approached with care. His methods emphasised empathy, plausibility, and subtlety: “If you visit their home, visit several others before and after... Avoid making the person feel they are being targeted.” He cautioned against overt language—never say “inform,” “witness,” or “intimidate”—and advised avoiding note-taking or financial inducements. Instead, he encouraged coded euphemisms: not “Your son is a terrorist,” but “Your son is taking up with a bad crowd.”⁴

This cultural sensitivity was central to Nairac’s method. He adapted his approach by demographic: political argument for younger men; appeals to family responsibility and financial stability for middle-aged individuals; and security, community, and legacy for the elderly. “Do you want hard men from the PIRA to rule your lives if we pull out?” he suggested as a rhetorical line for older locals. He urged fellow officers to acknowledge genuine grievances—“Denying a sincere complaint is worse than useless; it brands the speaker a liar”—while subtly redirecting sympathy toward young British soldiers killed in the line of duty.

The operational hub for these efforts was Bessbrook Mill, a converted linen factory in a once-quiet Quaker village. By the 1970s, it had become one of the most fortified military installations in the North. Helicopters departed constantly from its rooftop pads, ferrying troops into otherwise inaccessible terrain. Beneath its visible military function, however, lay a more secretive infrastructure of psychological operations and deception.

According to a 2025 Belfast Telegraph report, one of the most classified features of Bessbrook Mill was a “disguised informer room”—a fully constructed decoy flat designed to mimic a safehouse. With a garage entrance, living room, and kitchen complete with false chimney breasts and decorative fittings, the space functioned as a psychological ruse. It was designed not by police, but by military intelligence during the 1980s—likely the Force Research Unit (FRU)—to manage and manipulate informants under false pretences.

Informants were reportedly transported in the padded boots of unmarked cars, driven along confusing routes to distort their sense of geography, then delivered into the garage, made to believe they were in a civilian location. A concealed microphone in the ceiling transmitted audio to handlers in an adjacent room. The entire setup was a calculated illusion—a theatre of surveillance and control, where informants often remained unaware they were inside a military installation.

Nairac was among those stationed at the Mill. His quarters, according to former personnel, remain intact in the now-derelict upper floors.⁵

Two incidents from early 1976 and 1977 further illustrate the blurred boundaries of British covert activity during this period. In March 1976, republican activist Seán McKenna was allegedly abducted from his cottage in County Louth, just over the border. According to his own account, he was awoken at gunpoint by armed men, one of whom pressed a pistol to his head before marching him into the North. The operation bore the hallmarks of an SAS-led cross-border intervention, although it was never officially acknowledged. McKenna was held on remand for over a year and stood trial on 14 May 1977—the same day Nairac was abducted by the IRA. He would later participate in the 1980 hunger strike at Long Kesh, becoming one of the first prisoners to join the protest.⁶

The operation coincided with the deployment of both Nairac and — Julian “Tony” Ball, a senior SAS officer who commanded the 3 Brigade detachment of the Special Reconnaissance Unit (SRU), operating under the cover name “4 Field Survey Troop, Royal Engineers.” Ball, who would later be awarded both the Military Cross and the MBE, worked closely with Nairac, his second-in-command. Both men were reportedly commended for a series of high-profile arrests in South Armagh, though the nature of these operations has never been publicly disclosed.⁷

A second incident occurred the following month, in April 1977, involving the killing of Peter Cleary, a senior IRA member. Cleary was reportedly arrested during a covert British operation near his home in South Armagh and later shot and killed while in custody. Official sources claimed he had attempted to seize a weapon from a soldier guarding him. However, forensic evidence and witness testimony later cast doubt on this account. Cleary was delivered to a British Army base already deceased and placed directly into a body bag. Some reports suggest that Nairac had identified Cleary to the unit prior to the operation, contributing to ongoing allegations about his involvement in intelligence-led targeting and extrajudicial killings.

As British efforts to destabilise the IRA expanded beyond direct surveillance, another arena of covert operations emerged: Mid-Ulster. Unlike South Armagh, where the conflict was framed as counter-guerrilla warfare, Mid-Ulster became the theatre for a more sinister experiment in proxy violence.

The Triangle of Death

While South Armagh remained a crucible of republican resistance and British military surveillance, an equally deadly phase of the conflict was unfolding across Mid-Ulster, particularly within the rural triangle formed by Armagh, Portadown, and Dungannon. This region became known as the “Triangle of Death”, owing to the concentration of sectarian killings, car bombings, and targeted assassinations carried out by loyalist paramilitary groups, most notably the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), allegedly with the cooperation of members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), and British military intelligence.

This period saw the deployment of elite undercover units operating under civilian and military guises. Among them was the “4 Field Survey Troop, Royal Engineers”, itself staffed by personnel drawn from the Special Air Service (SAS). According to Fred Holroyd, a former British Army intelligence officer stationed in the region, this unit—active between 1973 and 1975—was composed of serving and former SAS soldiers engaged in deep-cover and deniable operations. Holroyd named both Julian “Tony” Ball and Captain Robert Nairac as key figures in these clandestine formations.8

Simultaneously, MI5’s influence in the Six Counties expanded, particularly in operations aimed at disrupting ceasefires and political negotiations.9 Within this shifting intelligence framework, Nairac’s role appears to have evolved beyond fieldwork: he reportedly operated as a liaison between British military intelligence, RUC Special Branch, and loyalist paramilitaries, navigating a covert ecosystem in which intelligence-gathering, psychological operations, and sectarian violence intersected.

Nairac was also growing disillusioned with the limitations of conventional military strategy. In an internal assessment, he argued that the British Army was unprepared for the nature of the conflict: “We are up against a sophisticated enemy… This is not a war that can be won by firepower alone.” He advocated instead for a doctrine grounded in intelligence dominance, infiltration, and disruption—a reflection of the “low-intensity operations” ethos that would come to define Britain’s counterinsurgency model. This shift would shape the remainder of his career—and, for some, implicate him in one of the most controversial chapters of the war.

At the centre of Mid-Ulster’s deadly violence was a covert alliance that came to be known as the Glenanne Gang: a loosely structured but operationally coordinated network of UVF paramilitaries, RUC officers, UDR personnel, and alleged British intelligence operatives. While lacking formal command hierarchies, the group reportedly operated with logistical and informational support from elements within the state. It has been linked to over 120 killings during the 1970s, most of them directed at Catholic civilians.

The gang’s name derived from a farm in Glenanne, County Armagh, owned by an RUC reservist, which served as a base of operations for planning attacks, storing weapons, and assembling explosives—often under the watch of state personnel. Among the most infamous attacks attributed to the group were the 1974 Dublin and Monaghan bombings (33 civilians killed), and the 1975 Miami Showband massacre, in which three musicians were murdered at a fake UDR checkpoint. Later investigations, including those by the Pat Finucane Centre and journalist Anne Cadwallader, revealed that many perpetrators were current or former members of the UDR and RUC, and that senior British intelligence figures were aware of their activities.

It is in this context that Robert Nairac’s reported connections to the Glenanne Gang have become the subject of ongoing scrutiny. In the 1991 documentary Hidden Hand: The Forgotten Massacre, a Yorkshire Television production, broadcast in July 1993, the narrator presented an explosive claim:

“We have evidence from police, military and loyalist sources which confirms the links between Nairac and the Portadown loyalist terrorists. And also that in May 1974, he was meeting with these paramilitaries, supplying them with arms and helping them plan acts of terrorism against republican targets. In particular, the three prime Dublin [bombing] suspects—Robert McConnell, Harris Boyle, and the man called ‘The Jackal’—were run before and after the Dublin bombings by Captain Nairac.”

The documentary claimed these allegations were corroborated by sources across multiple agencies:

“They include officers from RUC Special Branch, CID and Special Patrol Group; officers from the Garda Special Branch; and key senior loyalists who were in charge of the County Armagh paramilitaries of the day…”

Further claims were reported by journalist Frank Doherty, writing in the Sunday Business Post in July 1993. Citing unnamed sources in the Irish Army and Garda Síochána, Doherty alleged that forensic evidence from the Dublin and Monaghan bombings was transferred to RUC Special Branch, who in turn passed it to a British military intelligence officer later identified by Irish intelligence (G2) as having played a role in orchestrating the bombings.

“The RUC Special Branch gave the material to a British military intelligence man later identified by G2 (Irish military intelligence) officers as the man thought to have planned the attacks. He had control of the evidence for a number of days.”¹⁰

In a follow-up article in April 1999 titled “Dublin Bombings: New Revelations”, Doherty reported that:

“The Sunday Business Post has learned that at least one part of the vital [forensic] material was given to a captain who had close links with loyalists in what the British Army called ‘counter gangs’. He was a member of a secretive military intelligence unit whose command structure was located at RUC Special Branch headquarters in Belfast. His name, rank and appointment as detailed in the Irish Army intelligence file is known to the Sunday Business Post… The forensic material from Dublin was sent initially to a secret intelligence facility at Sprucefield near Lisburn. It was there that the man believed to be the mastermind behind the bombing had control of it.”¹¹

Although these claims remain unproven in a court of law, their consistency across multiple independent sources—military, journalistic, and republican—has placed Nairac’s legacy at the centre of long-standing allegations of collusion, intelligence-led terrorism, and proxy violence. Whether he was a principal architect or a field-level liaison, his proximity to the Glenanne network and the attacks they carried out continues to cast a long shadow over Britain’s covert war in Ireland.

Beyond allegations of collusion with loyalist forces, some of the most unsettling accusations against Nairac come from within the security establishment itself—suggesting that he may have orchestrated the exposure of his own assets to deepen infiltration into the IRA.

As the covert war escalated, the question of expendability—of who was sacrificed, and for what purpose—moved from abstract doctrine to chilling reality. Beyond allegations of collusion, some of the most disturbing claims involving Robert Nairac concern not just what he did to his enemies, but what he may have done to his allies.

Disposing of Informers

A recurring allegation within accounts of Britain’s covert war in Ireland is that certain loyalist paramilitaries and members of the security forces—once they had served their intelligence function—were deliberately exposed to the IRA, either to eliminate liabilities or to enhance the credibility of British agents operating undercover. Among the most disturbing claims involving Captain Robert Nairac is that he intentionally identified British and loyalist informers to republican forces in order to deepen his infiltration into the IRA.¹²

These claims were first publicly reported in The Sunday Times in 1999 and later expanded upon in An Phoblacht, where they were framed as part of a broader counterinsurgency doctrine that treated certain assets as expendable. According to these reports, Nairac passed the names of loyalist paramilitaries and UDR personnel to the IRA—individuals who had been involved in covert operations and who were later targeted and killed. Former RUC officer John Weir, whose role in the Glenanne Gang has been extensively documented, alleged that some of these agents were sacrificed to bolster the credibility of embedded operatives. In this model, spent collaborators were burned to gain deeper access to enemy networks.

An Phoblacht pushed the argument further, alleging that Nairac engaged in a form of double-agent theatre, selectively exchanging intelligence with the IRA to strengthen his standing. While morally indefensible, this tactic reflects methods used by British forces in previous colonial conflicts, such as in Kenya and Malaya, where pseudo-gangs, staged betrayals, and manipulated loyalties were deployed to fracture resistance movements from within.¹³

One of the most frequently cited examples of this alleged tactic is the killing of William Meaklin, a 39-year-old Protestant grocer and former RUC reservist abducted and killed near Newtownhamilton in August 1975. While the IRA claimed responsibility—stating that Meaklin had been passing intelligence to the British Army—multiple later accounts have suggested that he may have been deliberately exposed by Nairac.

Lost Lives, the definitive record of conflict-related deaths in Northern Ireland, offers a detailed summary of the incident in entry 1432:

“1432. August 13, 1975

William J. Meaklin, Armagh

Coleraine, Protestant, 39, married, grocer

A former member of the RUC reserve, his body was found two miles from his home in Newtownhamilton on the Castleblaney Road close to the border. The owner of a mobile shop, the IRA had kidnapped him the previous day near Crossmaglen where his van was recovered. He had apparently been tortured by the IRA, who accused him of gathering intelligence for the army. The Sunday Times (February 7, 1999) quoted a source who said that the general had been ‘given an awful lot to try and make him talk.’

A number of Catholics were killed in apparent revenge attacks after William Meaklin’s death. The bodies of two Catholics were found next to his home. The Irish Times reported that William Meaklin had belonged to the RUC reserve but had resigned to start his own business in Newtownhamilton at the time of his marriage, six months prior to his death. A number of Protestants were killed during the same period. William Meaklin was a member of the Orange Order. His cousin, Joseph McCullough, was killed by the IRA.

Many years later, it was suggested that the death of William Meaklin was part of a complex sequence of events. In February 1999 The Sunday Times said that relatives of several people killed in the immediate area were suspicious that William Meaklin’s death was the first in a chain which led to Captain Robert Nairac of military intelligence. Some of the relatives had informed the newspaper that the army officer had passed information to the IRA, which led to the deaths of several individuals who had been helping the security forces. At least one of the group, Robert McConnell, was said to have acted as a go-between for military intelligence and the UVF.” 14

The possibility that informers were knowingly “burned” to protect or elevate deep-cover operatives evokes the ruthless logic of Britain’s low-intensity warfare doctrine, where deniability, disruption, and psychological manipulation were paramount. Though definitive proof remains elusive, the convergence of journalistic, testimonial, and circumstantial evidence continues to raise troubling questions about the cost of Britain’s covert strategy—and the role Nairac may have played within it.

The Murder of John Francis Green

The killing of John Francis Green on 10 January 1975 remains one of the most controversial assassinations of ‘the Troubles’. Green, a senior IRA commander and Officer Commanding of the 2nd Battalion, North Armagh Brigade, was shot dead in a remote farmhouse in County Monaghan, more than a mile south of the Irish border, on the slopes of Mullyash Mountain.

Green’s murder occurred during the IRA’s 1974–75 ceasefire, declared on 20 December 1974 after encouraging talks between Protestant clergy and republican leaders in Feakle, County Clare. While both sides adhered to a fragile truce, elements within British military intelligence—including MI5—believed the ceasefire was a strategic ruse for IRA regrouping. These factions, hostile to political resolution, escalated covert operations.

According to later claims by whistleblower Captain Fred Holroyd, Captain Robert Nairac, then operating under British Army intelligence, was allegedly ordered to kill Green—viewed by British intelligence as a high-value republican target and symbolic threat to their counterinsurgency campaign.¹⁵

Green had been living in Monaghan’s border area while evading British forces following his dramatic escape from Long Kesh in 1973, where he had been interned after arrest in 1972.

During Christmas 1974, Green briefly returned to Lurgan. British soldiers knocked at his family home but did not enter, observing formalities that may have masked surveillance. Suspicious, Green quietly returned to Castleblayney, where he was staying with the McGurgan family—a large household with strong republican ties.

Around this time, the farmhouse of Green’s friend Gerry Carville, located in the remote Mullyash Mountains, became the subject of unusual attention. Carville’s house had been raided by Gardaí, circled by British Army helicopters, and previously visited by soldiers who crossed the border and were escorted back. Locals reported a white car—believed to be a Mercedes or Audi—seen in the area in the weeks before the killing.¹⁶

Carville’s home, located in a sparsely populated Protestant-Catholic borderland, was known as a quiet meeting point. Green had stayed there often. On the night of 10 January 1975, he drove to Carville’s home in a green Volkswagen, telling the McGurgans he would be back shortly. The weather was cold and stormy.

According to Carville’s account, Green arrived at the farmhouse around 6:30 p.m. and was sent briefly to fetch milk from a neighbour. After returning and having tea, Carville left Green alone in the house while he went to tend to nearby cattle with another visitor, Tommy Laverty.

When Carville returned just before 7:30 p.m., he found Green lying dead on his back in the front hallway. The door had been kicked in. Green had been shot multiple times at close range. A shocked Carville ran to alert neighbours. A Garda investigation later confirmed that the front door frame bore visible cracks consistent with forced entry, and Green had been shot with two weapons—a 9mm Luger and a Spanish-made Star automatic pistol. Several live rounds had been left on top of the body—a chilling signature.

According to former intelligence officer Fred Holroyd, Captain Robert Nairac not only claimed responsibility for Green’s killing but described it in detail during a meeting in Portadown. Holroyd later recounted that Nairac produced a colour Polaroid photograph of Green’s corpse, taken shortly after the killing. This was highly unusual; Gardaí at the time had only black-and-white photographic equipment, and no Garda officer in the Monaghan region was known to carry a Polaroid camera.

In his account, Nairac explained that he and two associates had crossed the border, watched Green through an uncurtained window, and then stormed the farmhouse, shooting Green repeatedly, emptying one weapon into his body as he lay dying. Forensic reports confirmed that two weapons were used, one of which was later linked to multiple sectarian murders, including the Miami Showband massacre.

This Spanish-made Star pistol had reportedly once belonged to a UDR soldier, Robert Winters, a founding member of the UVF, who claimed the weapon was stolen during a mugging in Portadown. The provenance of the weapon, and its later use in multiple loyalist atrocities, reinforced suspicions that Green’s murder was part of a wider pattern of state-enabled killings carried out by loyalist death squads in coordination with British intelligence.

Later testimony by former RUC officer John Weir identified Green’s killers as Robin Jackson (known as “The Jackal”), Robert McConnell (a UDR soldier), and Harris Boyle (a UVF member who died during the Miami Showband bombing). Weir described the unit as a loyalist death squad directed by British undercover units, including the SAS, and claimed that the Green assassination had been planned not as a targeted hit against Green specifically, but as an attempted killing of a local farmer, Gerry Carville, suspected of sheltering IRA operatives.

Green’s death — having occurred during a ceasefire — sparked large public mourning, including funeral processions in Monaghan and Lurgan, marked by full IRA guards of honour and widespread closure of businesses. Gardaí and even RUC officers saluted his cortège as it passed.¹⁷

During the 1977 trial of IRA members charged with Nairac’s killing, it emerged that a personal pistol—in addition to his standard-issue Browning—had been recovered from his quarters. Some suspect this was the same weapon used in Green’s murder, although this has never been proven. It also remains unclear whether Nairac himself pulled the trigger or simply supplied arms and oversight to a loyalist paramilitary unit with which he had documented contact.

More than four decades after Green’s death, his family’s calls for an inquiry have gone unanswered. What is known is that a man—married with three children—was executed in violation of international law, on sovereign Irish soil, during a ceasefire, by a group operating with the apparent support of the British state.

Despite mounting evidence, the British government has never acknowledged involvement in Green’s murder. Efforts to discredit Holroyd and suppress discussion of the Polaroid photograph included media manipulation. In 1987, The Independent newspaper published a counter-narrative suggesting the Gardaí had taken the photo, but senior Garda sources strongly denied this. Critics accused the article of serving as an MI5 or RUC propaganda piece, aimed at undermining Holroyd and shielding Nairac.

Green was buried in the Republican Plot in Lurgan, accompanied by an IRA guard of honour and thousands of mourners. Yet the truth behind his killing, and the precise role of Robert Nairac, remains entangled in a web of state secrecy, media manipulation, and political evasion.

This killing, too, reflects the broader operational pattern seen in Nairac’s career: extrajudicial action, covert presence across borders, and a strategic use of loyalist proxies.

Miami Showband Massacre

The Barron Report—an official investigation commissioned by the Irish government into the 1974 Dublin and Monaghan bombings—also addressed wider allegations of collusion between British security forces and loyalist paramilitaries. It cited claims that certain elements within the British Army and intelligence services had used loyalist groups as a “friendly guerrilla force”, supplying them with intelligence, logistical support, and target information. The report specifically referenced Captain Robert Nairac in this context, placing him at the centre of these covert relationships.¹⁸

The following account of the 1975 Miami Showband Massacre is drawn from The Miami Showband Massacre by Stephen Travers and Neil Fetherstonhaugh, published by Hodder Headline Ireland Ltd. The narrative offers a first-hand and deeply personal perspective on the attack, reconstructed from Travers’s own testimony, alongside corroborating evidence and journalistic investigations.

On the night of 31 July 1975, members of the Miami Showband, one of Ireland’s most beloved musical groups, were ambushed on their return to Dublin after a gig in Banbridge, County Down. The band’s minibus was stopped by what appeared to be a routine British Army checkpoint at Buskhill, outside Newry. In reality, it was a UVF ambush, carried out by loyalist gunmen, several of whom were also serving members of the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR).

Inside the van, trumpeter Brian McCoy noticed a red light waving from the roadside—a common checkpoint signal. “We’re being pulled over,” he told the others. This wasn’t unusual. The band had been stopped before by both British and UDR patrols. “There would be the usual chat,” recalled Stephen Travers, the band’s new 24-year-old bass guitarist. “Sometimes they’d even recognise us and ask for autographs.”

But this time was different. As the van came to a stop and McCoy rolled down the window, armed men—posing as soldiers—surrounded the vehicle. Travers remembers one man leaning casually against a tree, rifle pointed at the van. The band members were ordered out and lined up along the roadside. One of the attackers, Thomas Crozier, began taking names and addresses in a notebook. Strangely, the mood was relaxed. The men cracked jokes. “Fran [O’Toole] said they probably didn’t like being out there either,” Travers recalled. “They laughed. I still can’t understand that. They were joking—knowing what they were about to do.”

Suddenly, a car pulled up behind the minibus. A new figure emerged and everything changed. He wasn’t dressed like the others. He wore smart, light-coloured combat trousers with multiple pockets, a fitted smock, and a distinctive beret that was a different shade from the rest. He moved with precision and authority. “He had all the bearings of command,” said Travers. “Cool, professional—he looked like Action Man.”

Most notably, he spoke with a clipped, well-spoken English accent. “It was a commanding tone—the voice of someone used to giving orders.” The men around him stiffened and fell into line. He didn’t address the band directly but ordered, via another man, that Crozier should ask for dates of birth instead of names and addresses. McCoy turned to Travers and whispered, “It’s okay Stephen, this is British Army.” As a Protestant from the North, McCoy was familiar with security procedures. Both he and fellow bandmate Des McAlea believed this was a legitimate British Army–UDR joint checkpoint. Travers, reassured, simply grew annoyed at the delay.

Then he heard the back of the minibus being opened. His concern turned to frustration. “I had a rare guitar—a transparent Dan Armstrong Plexiglas bass—and I didn’t want it being mishandled.” He stepped out of line and approached the rear of the van. One of the gunmen asked if there were any valuables inside. Travers replied that it was just equipment. Then, suddenly, one of the gunmen punched him hard in the kidneys. The blow knocked the wind out of him. “It caught me off-guard as well as hurting me.” He was shoved back into line, now standing beside Brian McCoy. At that moment, Travers realised something was wrong.

While two gunmen rummaged in the van, two others placed a 10-pound bomb under the driver’s seat, intending it to detonate later and frame the band as IRA bomb smugglers. But the device exploded prematurely. The blast instantly killed Boyle and Sommerville, the two UVF men planting the bomb. Their bodies were torn apart—one torso thrown nearly 100 yards. The explosion ripped the minibus in two and hurled the musicians through the air. “I was able to count every branch as I passed through,” Travers later recalled of the sensation of being flung through the bushes.

Then came gunfire. The UVF gunmen opened fire with submachine guns and pistols in blind panic. Bullets tore through flesh and bone. Fran O’Toole, Tony Geraghty, and Brian McCoy were all gunned down. Travers, struck by a dum-dum bullet, was badly wounded but remained conscious. “It entered through my hip and tore through everything—organs, arteries—before exiting under my arm.”

He landed in a field. Tony and Fran tried to lift him. “One of them was crying.” They dragged him a short distance before being forced to abandon him and run. “I heard them screaming, begging not to be killed. Then a long burst of gunfire. And then... silence.”

Travers lay still. He heard footsteps—one of the gunmen approaching. “I had two choices,” he later recalled. “Beg for my life or pretend to be dead. I chose to stay down.” The gunman kicked a body nearby—McCoy’s—then approached Travers. At that moment, a voice from the road shouted: “Come on, those bastards are dead. I got them with dum-dums.” The footsteps paused. Then turned and walked away.

Bleeding out, Travers had been shot through the torso with a modified high-velocity round designed to cause maximum injury. He was taken to Daisy Hill Hospital, then transferred to the Republic. Months later, the band attempted to reform in tribute, but Travers soon left Ireland, deeply traumatised.

In the years that followed, Travers became convinced that the commanding figure—the well-spoken officer who changed the mood at the scene—was Captain Robert Nairac. “He had a clipped English accent, military posture, and was clearly in charge,” Travers said. “I am convinced it was Nairac.”

That belief is echoed in declassified documents, legal testimony, and statements from former intelligence personnel. It is now alleged that Nairac supplied the UVF with the uniforms, weapons, and intelligence needed for the ambush—and that he was present at the scene, directing the operation.

The Star pistol used in the earlier killing of IRA member John Francis Green was later linked to the same weapons cache used in the massacre. Many of the killers were members of both the UVF and the UDR. They were later tied to the Glenanne Gang—a covert network of loyalist paramilitaries, RUC officers, and British military intelligence, responsible for scores of sectarian killings during the Troubles.

A 2020 civil case brought by victims’ families disclosed a document identifying Nairac as the operational planner behind the massacre. The original goal was to stage the bombing as a failed IRA mission, discrediting the band and fuelling sectarian outrage. That plan failed, but for decades, British authorities denied official involvement.

Stephen Travers has spent much of his life campaigning for the truth. “The British government didn’t just allow it,” he has said. “They ordered it.”

The Miami Showband massacre encapsulated the lethal convergence of military intelligence and loyalist terrorism—and for many, it cemented the shadowy role of Robert Nairac at the heart of Britain’s covert campaign. Just two years later, that campaign would end in blood—his own.

Robert Nairac’s Final Operation

Robert Nairac’s final 48 hours begin, according to Kerr's book Betryal: The Murder of Robert Nairac GC, with a meeting at Newry Courthouse on Friday 13 May 1977. The meeting is with an intermediary acting on behalf of the suspect informer Nairac attempts to meet the next day – in Dromintee.¹⁹

On Saturday morning, 14 May 1977, Nairac sets off from the busy and sprawling Bessbrook Mill army base and travelled across the border for trout fishing in the South. He returns to Bessbrook Mill at around 4:00 PM.

In Betrayal: The Murder of Robert Nairac GC, Kerr describes how Nairac spent the afternoon in seclusion. He took a call, withdrew to his quarters, and reportedly “said very little to anyone else” before leaving.²⁰

Nairac leaves Bessbrook Mill at 9:25 PM and drives alone to the Three Steps Inn in Dromintee, County Armagh. He was behind the wheel of a red Triumph Toledo, a vehicle discreetly modified for undercover surveillance. Inside, it carried a concealed microphone, a high-frequency radio transmitter, and a panic button wired to alert nearby units if triggered. The license plate, CIB 4253, was partially and deliberately obscured with mud.

He makes three radio check-ins back to base during his journey.

He arrives at the Three Steps Inn and parks in the pub’s gravel car park, makes his final radio check-in at 9:59 PM and enters the pub alone.

The Three Steps Inn, where Nairac made his final public appearance, held particular significance in the local geography of the conflict. Located near the village of Dromintee in County Armagh, it sat just two miles from the Irish border and served as a well-known gathering place for local republicans.

The bungalow-style pub stood on historically charged ground. It had been built on the site of McGuill’s Public House, which was burned down in 1922 by the Royal Ulster Constabulary after the premises were reportedly used by republicans to stage ambushes against police patrols. In the 19th century, the original building had served as a soup kitchen for victims of the Great Famine. By the 1970s, the interior of the bar was adorned with murals celebrating Irish republican and nationalist history—a visual testament to the area's strong political identity. The pub’s reputation made it an unlikely choice for any British soldier, let alone an intelligence officer.

Although he made several radio check-ins with Bessbrook using his call sign “48 Oscar,” Nairac was operating without immediate backup.

Dressed in civilian clothing—a black donkey jacket, flared grey trousers, and worn suede shoes—Nairac cut a confident figure. Beneath the jacket, however, he carried a Browning 9mm pistol with notable custom modifications: the butt had been filed down to minimise bulk and aid concealment, and the safety catch had been enlarged for quicker handling under pressure. The pistol was secured in a personally purchased shoulder holster, allowing it to hang discretely beneath his outer layer—standard tradecraft for an undercover intelligence officer.

The Three Steps Inn was bustling that night, with an estimated 150 to 200 patrons and live music provided by John Murphy’s Band. Nairac arrived alone, parked his red Triumph Toledo at the rear of the car park.

Robert Nairac entered the pub using the cover identity of “Danny McErlean”—a purported Belfast native and former member of the Official IRA. To reinforce the alias, Nairac reportedly carried forged identification papers, including a Northern Irish driving licence bearing the McErlean name and a Belfast address.

According to Bandit Country author Toby Harnden, his objective that night was to meet Séamus Murphy, a well-known former Official IRA figure then working in local government. But Murphy, by that time, had fallen out of favour and was no longer welcome at the Three Steps. Nairac, who would likely have been aware of this, appears to have invoked Murphy’s name as a convenient pretext for being there—his real objective probably lay elsewhere.

Inside the pub in Dromintee, County Armagh, Nairac appeared relaxed, blending in as best he could. He ordered drinks, chatted with patrons, and maintained a low profile, but his unfamiliarity with the area, manner of speech, and the general air of being out of place began to raise suspicions. He ordered a pint of Guinness and was observed speaking with two men who would later be identified as his abductors.

At one point during the evening, he appeared to misplace a packet of Major cigarettes—an act many now believe was a recognition signal. The same behaviour had been noted on a previous night, lending weight to the idea that it was intentional. No contact came of it.

Unbeknownst to him, local suspicions were already running high. Rumours linked him to recent British operations and the deaths of several IRA members, including John Francis Green, Seamus Harvey and Peter Cleary. His manner—strikingly out of place, articulate, and confident—only deepened community wariness.

Among the patrons at the pub that night was Kathleen Johnston, a local woman whose observations were later recorded by Martin Dillon in The Dirty War:

“At around 9.00 pm my husband Patrick and I went down to the Three Steps for a drink. A neighbour had had a drink too many and kept coming back and forward to us. I have seen a photograph of a man [she later identified as Nairac] and he was sitting on the other side of the steps to the balcony watching the television and his attention was drawn to us because of the actions of this drunken neighbour. The man smiled over at us. Later this man was still at the bar. I saw him go over to the counter. He was acting as if he had lost something. I spoke to him asking if he had mislaid anything and he told me he had lost his cigarettes. He went back and sat down. My husband and I left the pub at about 10.00 pm. As we were leaving, the man in the photograph was also leaving. He smiled at us and walked up to his car which was parked at the top of the car park. I saw him open the door of his car but that is all I saw.”²¹

Earlier in the evening, Nairac had reportedly asked a young woman how to cross the border without encountering checkpoints. She passed this onto others in the pub. To confirm suspicions, she was encouraged to invite him to dance. He declined—but instead offered to sing.

At around 11:15 p.m, he took to the stage and sang “The Broad Black Brimmer”, a republican ballad narrating the story of a son inheriting his father’s IRA uniform and legacy. Despite the performance, locals remained unconvinced. “It was a strange choice for someone trying not to stand out,” one later remarked.

Nairac fails to check-in back to Bessbrook Mill at the scheduled radio time.

As the night wore on and patrons began to leave, Nairac lingered, chatting with the band as they packed away their equipment. When offered a lift, he declined—despite the noticeable presence of two young men, who were waiting near the exit with apparent intent.

Accounts diverge on Nairac’s movements late that night. Some suggest he made repeated trips to the lavatory, possibly attempting to destroy compromising material. Others, such as Terry McCormack, later claimed he never went to the bathroom at all.

According to Kerr’s book, Nairac was observed making repetitive trips to the lavatory at the Three Steps Inn – prompting suggestions that he may have been trying to destroy evidence that might reveal his true identity and purpose. In one account, two of his abductors reportedly followed Nairac into the lavatory at one point and questioned him as he washed his hands.

Around midnight, a disturbance broke out in the car park. Edmund Murphy, one of the band members, heard raised voices and assumed it was a typical barroom altercation.

According to an interview on BBC Spotlight, Terry McCormack—one of those who confronted Nairac—later recalled, contradicting other accounts:

“It was decided that when he went to the bathroom, we would approach him there to find out who he really was—but he never went to the bathroom.

Around 12 o’clock, he was seen leaving the pub. I followed him out after telling someone to watch my back. I caught up to him halfway across the carpark. I put my finger to the back of his head, hoping he’d think it was a gun, and asked for his license.

He turned quickly—I punched him in the face. That’s when I heard something hit the ground. I shouted to the others, ‘He’s got a gun!’ People watching from outside the Three Steps ran to join me.”

A violent struggle broke out. Blood and clumps of hair were later found near the parked Toledo. Nairac had no opportunity to reach for his pistol or press the panic button concealed in the dashboard.

“He was on the ground and I was holding him there as best I could. My friends arrived and they started punching and kicking him.

The gun was found beside the car. It was picked up, put to Nairac’s head, and he was told he was going to be questioned.”²²

He was bundled into a waiting bronze Ford Cortina and driven across the border into the Republic. According to later testimony, British soldiers nearby witnessed the abduction but did not intervene.

In 2025, UTV revealed that British Army soldiers witnessed the abduction of Captain Robert Nairac on the night of 14 May 1977. According to the report—published amid renewed efforts to locate his remains in County Louth—Nairac was under covert observation by British forces conducting surveillance on republican activity at the Three Steps Inn in Dromintee.

Well-placed military sources confirmed that a covert Army operation was active in the area at the time of the kidnapping. The soldiers, dug in close to the pub’s car park, had been instructed to observe but not intervene. These were not Special Forces, but ordinary infantrymen assigned to gather intelligence.

While Nairac had checked in with Bessbrook Mill earlier that evening, it remains unclear whether those observing the pub recognised him—either as a fellow soldier or as the specific officer operating undercover.

The ITV report noted:

“Covert soldiers observing the movements of republicans from a pub witnessed the Grenadier Guards abduction in May 1977. The ordinary soldiers were instructed to observe but not interact. They were dug in right beside the car park.”²³

What followed occurred across the border in County Louth, in a remote area familiar to the local IRA. There, over the course of several hours, Captain Nairac was interrogated and ultimately killed—an outcome shaped as much by his suspected identity as by the fraught context of the conflict itself.

The Killing

Nairac’s captors drove him across the border into Ravensdale Forest, County Louth, eventually stopping near the Flurry Bridge, a wooded and remote area commonly used for covert IRA activity.

At the bridge, signs of a violent confrontation were later found: a bullet embedded in the stonework, bloodstains, and broken teeth. According to witness testimony, Nairac made a sudden attempt to resist. In the scuffle that followed, Terry McCormack was reportedly grazed by a ricocheted round. The pistol Nairac had carried in a concealed holster had earlier been seized at the scene of his abduction.

Nairac refused to identify himself. He insisted he was “Danny McErlean,” a Belfast native and member of the Official IRA, a faction known locally as “the Stickies.” The alias, however, only deepened suspicion—especially when he failed to give convincing answers about local figures and places in Dundalk. The real McErlean would later be murdered in circumstances suggesting confusion or reprisal related to this incident.

Although most of those involved in the abduction were not IRA members, one figure—Liam Townson, an active member of the Provisional IRA—was called in from Dundalk. Along the way, he stopped to retrieve a .32 calibre revolver from an arms cache within a stone wall.

Townson took over the questioning. By this point, Nairac had already been subjected to a sustained and brutal interrogation.

McCormack later stated that he told Nairac he would be executed if he did not reveal his identity. When he refused, a priest was requested but did not arrive. McCormack impersonated a priest in a final attempt to elicit a confession. Nairac, still bloodied and disoriented, reportedly responded:

“Bless me Father, for I have sinned…”²⁴

McCormack walked away from the scene. As he did, he said he heard several gunshots.

The next morning, the alarm was raised by the British army at 5:43 AM. The Gardaí and the RUC are notified and the Gardaí begin trying to piece events together. Forensic evidence—including blood, spent cartridges, and personal effects—was collected at the bridge.

On Monday, 16th May 1977, The IRA issued a statement claiming it had interrogated and executed Captain Robert Nairac. Two days later, on Wednesday, anglers direct Gardaí to a location near Ravensdale Forest where signs of struggle are found—blood, hair, and spent rounds—confirming the site of Nairac’s killing. That Friday, a photograph of Nairac—taken months earlier in Ardoyne—appeared in Irish republican publications.

Nairac’s body, however, was and to this date, has never been recovered.

According to McCormack and others, the body was initially buried near the site but was later moved at the request of a local farmer, who discovered animal activity near the shallow grave. The remains were quietly removed that same night.

This belief was echoed by former SAS Deputy Commander Clive Fairweather, who told BBC Spotlight:

“I understand that his body was fairly quickly moved that night after the event, and buried somewhere in an unmarked grave.”

Kevin Crilly, arrested years later in connection with the case, also told Spotlight:

“I heard it [the body] was moved.”

Author Toby Harnden, in Bandit Country, suggested the body may have been disposed of at the Ravensdale Anglo-Irish Meat Plant, a site connected to known republican activity. Former IRA member Eamon Collins—himself later executed by the IRA for informing—suggested that Nairac’s remains may have been destroyed and rendered untraceable, possibly to eliminate any forensic risk or symbolic recovery.

In the days that followed, Liam Townson was arrested and led Gardaí to a weapons cache in Ravensdale containing Nairac’s Browning pistol. A bloodstained pullover found nearby was later confirmed through forensic testing to contain Nairac’s blood type—despite initial British Army claims that no such information was recorded.

Townson was tried in the South and sentenced to life imprisonment for murder and firearms offences.

In the North, five men were tried and convicted by a Diplock court in 1978:

Gerard Fearon – Life for murder, plus 22 years for related offences.

Thomas Morgan – Life for murder (indefinite detention).

Daniel O’Rourke – 10 years for manslaughter, 7 years for kidnapping.

Michael McCoy – 5 years for kidnapping.

Owen Rocks – 3 years for withholding information.

Most of the men served comparatively short sentences and were released by the early 1980s.

Files uncovered by the Belfast Telegraph at the National Archives in Kew suggest that the Ministry of Defence was deeply uneasy about apprehending Nairac’s killers, fearing that any subsequent inquiry might expose the true nature of his covert mission and the intentions behind his movements on the night of 14 May 1977.

Within 24 hours of Robert Nairac’s disappearance, SAS officers entered his quarters at Bessbrook Mill and removed classified materials. According to Alistair Kerr, one item—never publicly identified—was deemed “very significant.” The room, located within the living quarters of the sprawling military base, was briefly sealed and later cleared, its contents dismissed as “rubbish.” Today, it lies abandoned—windows broken, plaster crumbling, dead pigeons strewn across the floor—a stark contrast to the intelligence nerve centre it once housed.

Newly uncovered cables and memoranda obtained by the Belfast Telegraph from the National Archives reveal that the British Ambassador in Dublin was informed the very next day that Nairac had been involved in “covert operations” in Dromintee and had served as “a liaison officer with the SAS.” Despite this, British officials urged discretion, concerned that pressuring the Irish government could attract premature scrutiny—and with it, questions about what Nairac had truly been doing that night.

By July 1977, just two months after the killing, internal Whitehall correspondence showed growing unease. Senior Ministry of Defence officials began preparing “defensive press briefings” that denied any SAS affiliation, despite the fact that military witnesses at the subsequent trials included both a G2 intelligence officer and the SAS second-in-command at Bessbrook. The inconsistency was not lost on British diplomats, who scrambled to maintain the official narrative that Nairac had no connection to special forces.

By February 1978, as further prosecutions advanced in the North, the extent of official secrecy became more explicit. A confidential memo from the Secretary of State’s private secretary recorded the Ministry of Defence’s refusal to confirm that Nairac had gone to the Three Steps Inn to meet an informer. The reason: doing so would risk not only compromising sources, but also exposing Britain's broader informant-handling infrastructure.

If pressed in court, prosecutors were advised to suggest that Nairac had simply gone to the pub “to see what he could pick up from locals.” Any deeper acknowledgment, one official warned, could open the door to allegations that he was involved in a “secret assassination squad.”²⁵

So concerned were officials about the possible fallout that one internal recommendation proposed abandoning the prosecution entirely if it risked revealing operational details. The trial ultimately proceeded, resulting in multiple convictions—but the episode laid bare the extraordinary lengths to which the British state was willing to go to protect the secrecy surrounding its covert operations.

What remains most telling is not only the concealment, but the precision of what was concealed. One internal memo warned: “This might lead to a request for the name(s) of the informant(s) which could not be disclosed.” That line alone strongly suggests that the British government knew exactly whom Nairac had been sent to meet, but has chosen never to acknowledge it.

To this day, the identity of the intended contact remains unconfirmed, and the objective of Nairac’s final mission is officially undisclosed. Yet the accumulated evidence increasingly supports what has long been held in republican memory: that Nairac’s last operation was no freelance venture—it was a planned, high-level intelligence mission, one that the British state has worked meticulously to obscure.

The Disappeared

Toby Harnden, author of Bandit Country, later argued in an Instagram post that the most likely explanation for the continued absence of Captain Nairac’s remains is that the IRA deliberately destroyed the body. Writing in Bandit Country, he observed:

“More than 22 years after his death, Nairac's body has still not been found. According to both republican and security sources, the most likely explanation is that the body was destroyed by the IRA—either to avoid negative propaganda or due to the severity of the injuries he had sustained.”²⁶

Harnden notes that Liam Fagan—who later joined Republican Sinn Féin after the 1986 split and died three years later—is believed to have been tasked with disposing of the body. “The secret of what happened to Nairac’s body probably died with him,” Harnden concludes.

Harnden also links the suspected disposal site to the Anglo-Irish Meat Company in Ravensdale. In 1976, a year before Nairac’s disappearance, five local residents who had objected to planning permission for the factory’s expansion reportedly received death threats from masked gunmen. A note delivered to their homes read: “Withdraw your objections to the factory extension or a member of your families will be dead in 24 hours.”

Years later, in 1983, Eamon Collins—a former IRA intelligence officer turned informer, who was later executed by the IRA—stayed at a safehouse in Dundalk owned by a man allegedly involved in disposing of Nairac’s body at the meat plant. Collins recounted that several IRA members had worked at the factory on a short-term basis, apparently without the knowledge of its owners. One told him:

“They scalped him, cut out his innards, then turned him into meat and bone meal. I think they must have burnt the scalp and the giblets.” ²⁷

Despite decades of search efforts, appeals by senior political and religious figures, and the establishment of the Independent Commission for the Location of Victims’ Remains (ICLVR), his body has never been recovered.

In Betrayal: The Murder of Robert Nairac GC, author Alistair Kerr presents the most comprehensive reconstruction of what reportedly happened in the aftermath of the killing. Drawing on interviews, court records, and former IRA sources, Kerr describes how the murder was not sanctioned by the IRA’s central leadership, but carried out independently by local members who suspected Nairac was a soldier or loyalist operative.

The local IRA command, once informed of the killing, was reportedly furious. They were now responsible for managing the fallout of an unauthorised act that posed serious political and operational risks. The priority quickly became the disposal of the body—discreetly, swiftly, and in a manner that would prevent it from becoming a propaganda liability.

The initial burial took place in a shallow grave—roughly two feet deep—on farmland belonging to a known republican sympathiser. But within days, animals uncovered parts of the decomposing body. The landowner, unwilling to be implicated, demanded that the IRA remove the remains. According to Kerr, he threatened to alert the Gardaí unless it was done immediately.²⁸

Responsibility for the reburial reportedly fell to a second group of volunteers, led by Liam Fagan, a smallholder and local republican who had longstanding links to the movement. Crucially, Toby Harnden also names Fagan in Bandit Country as the man entrusted with disposing of the body, citing multiple republican and security sources. Fagan, who died in 1989, had also provided shelter to Liam Townson, one of Nairac’s abductors. Townson was arrested on Fagan’s farm shortly after the killing.

The second burial was said to have taken place either on Fagan’s land or within nearby Ravensdale Forest, a remote and wooded area straddling the border. According to Kerr, “the body was moved by hand across the fields” and reinterred in a more secluded location, this time buried four feet below the surface. The operation avoided roads and vehicles to reduce the risk of detection by Gardaí or British patrols.

Both Kerr and Harnden note that the burial site was known only to a small number of people, some of whom are believed to still be alive. Harnden writes that “the secret of what happened to Nairac’s body probably died with Liam Fagan,” though suggests that others—including family members or fellow volunteers—may still hold that knowledge.

In this version of events, there was never any serious attempt to destroy the body using industrial methods, as other accounts have occasionally suggested. Kerr dismisses the meat factory theory—popularised by Eamon Collins—as improbable given the rapid Garda searches of such locations in the days that followed.

In April 1999, following an 18-month internal investigation, the IRA issued a statement identifying the burial sites of nine individuals it had executed and secretly buried between 1972 and 1981. The statement, published by An Phoblacht, expressed regret for the prolonged anguish caused to the families and emphasised that the process had been initiated for humanitarian reasons.²⁹

Importantly, while the IRA took responsibility for those nine "disappeared" individuals—most of whom were informers or alleged traitors—it specifically did not include Captain Robert Nairac among them. Instead, an IRA spokesperson acknowledged that efforts had been made to locate his remains but that they had failed to do so. This admission marked the IRA’s only formal reference to Nairac’s death in the context of the "Disappeared" and confirmed that his burial site remained unknown.

The IRA reiterated that the issue was humanitarian and rejected claims of cynicism surrounding the timing of the disclosure. The omission of Nairac from the list underscored the unique secrecy that continues to surround the circumstances of his execution and the disposal of his body.

While the IRA has stated that it was unable to locate Captain Nairac’s remains, the British state remained conspicuously silent about the specifics of his final operation. The lack of official disclosure—and the efforts to manage the narrative—highlight the enduring sensitivity surrounding his activities and the broader context in which they occurred.

In the autumn of 2024, a renewed search for Robert Nairac’s remains was conducted at Faughart in County Louth, but no trace of the body was found. By the spring of 2025, an IRA source reportedly stated that Nairac’s body would never be recovered.

The fate of Nairac’s remains, still unresolved, mirrors the silence that continues to surround his mission, raising questions not just about the man—but about the system he served.

The Legacy of Nairac & Official Silence

In the nationalist and republican consciousness, Robert Nairac’s name remains synonymous with collusion, deception, and covert violence. Unlike the British portrayal of him as a romantic idealist and war hero—enshrined by the posthumous awarding of the George Cross—republican communities remember him as a field commander of death squads, a liaison between the British state and loyalist killers.

In areas like South Armagh, he is not spoken of as a soldier but as an agent provocateur, believed to have orchestrated intelligence-driven killings, and possibly even manipulated the deaths of informers and enemies alike to maintain his cover. His alleged involvement in setting up figures later killed by the IRA has been passed down in oral tradition, folklore, and unresolved trauma.

IRA statements, such as the one released in 1998 in the context of the peace process, do not deny the killing of Nairac, but justify it as an act of war—framed within a narrative of defending communities from state-sponsored infiltration and manipulation.

“10 December 1998

Oglaigh na hEireann investigations into the whereabouts of the bodies of a small number of people killed and buried by the IRA over 20 years ago are continuing.

We urge anyone with information which may be of assistance in identifying the location of the grave of any of these people to pass this information to ourselves or to the family of the person concerned.

Any information passed to the IRA concerning these matters will be treated in strictest confidence and without prejudice to the source.

P O'Neill, Irish Republican Publicity Bureau, Dublin.”

Nairac’s remains have still not been found – still “disappeared” along with two others from the conflict, Columba McVeigh and Joe Lynskey.

The posthumous narrative of Captain Robert Nairac has been carefully curated by the British establishment. Official tributes, the George Cross citation, and parliamentary speeches have cast him as a martyr—courageous, misunderstood, and tragically killed in service of peace. His name appears on British war memorials, and his life has been subject to television documentaries and sympathetic biographies.

Yet this state-sponsored remembrance sits in stark contrast to the findings of journalists, human rights organisations, and former intelligence officers. The Belfast Telegraph, Panorama, and Spotlight have all revealed layers of secrecy surrounding his mission, the suspicious conduct of the Ministry of Defence following his death, and the extent to which his operational brief was withheld even during the criminal trials that followed.

Internal documents now confirm that British officials feared the fallout from public knowledge of his real mission—to meet an informer—and that the government considered dropping the trials of his abductors to avoid scrutiny of Nairac’s covert duties.

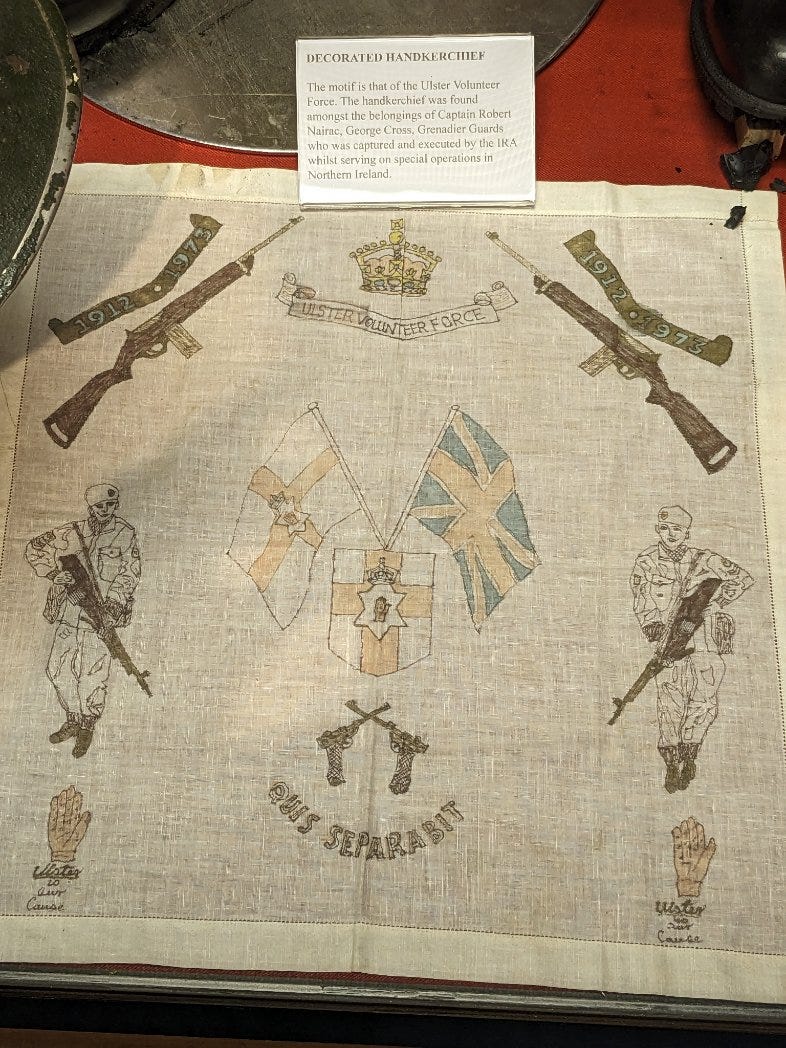

Nairac’s legacy is thus dual and unresolved: a British hero in official memory, and a sinister architect of clandestine violence in the republican record. His story, like so much of the Troubles, remains contested—caught between erasure and revelation, myth and memory. Among the few physical artefacts that remain from his covert career is a handcrafted handkerchief bearing the insignia of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), quietly held in the collection of the Grenadier Guards Museum. Its presence —unexplained—serves as a muted but evocative symbol of the ambiguous loyalties, covert entanglements, and enduring secrecy that continue to shape how Robert Nairac is remembered.

Appendix

Talking to People in South Armagh — by Robert Nairac

References

¹ A.F.N. Clarke, Contact (London: Pan Books, 1984), 76.

² Roger Faligot, Britain’s Military Strategy in Ireland: The Kitson Experiment (London: Zed Books, 1983), 47.

³ Staff Reporter. “Cops Launch Major Investigation of MRF Drive-By Killer Team.” Belfast Media, 2 December 2015. https://belfastmedia.com/cops-launch-major-investigation-of-mrf-drive-by-killer-team

⁴ Robert Nairac, Talking to People in South Armagh, unpublished internal British Army briefing paper, circa 1977.

⁵ Sam McBride, “An inside look at the informer room in what was once Army’s south Armagh fortress... and now a crumbling relic,” Belfast Telegraph, April 14, 2025. https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/an-inside-look-at-the-informer-room-in-what-was-once-armys-south-armagh-fortress-and-now-a-crumbling-relic/a168933373.html

⁶ Fr Denis Faul and Fr Raymond Murray, SAS Terrorism – The Assassin’s Glove, July 1976, p. 6.

⁷John Parker, Death of a Hero: Captain Robert Nairac, GC and the undercover war in Northern Ireland (Metro Books, 1999), p. 21.

8 Fred Holroyd, letter to The Guardian, 13 May 1987 (unpublished). The full text was later reproduced in Lobster magazine, Issue 13, June 1987.

9 John Parker, Death of a Hero: Captain Robert Nairac, GC and the undercover war in Northern Ireland, Metro Publishing, 1999, p. 71.

¹⁰ Frank Doherty, “Bombing Evidence Was Given to British,” Sunday Business Post, 11 July 1993.

¹¹ Frank Doherty, “Dublin Bombings: New Revelations,” Sunday Business Post, 4 April 1999.

¹² David McKittrick, Seamus Kelters, Brian Feeney, Chris Thornton, and David McVea, Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children Who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles (Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 1999), p. 562.

¹³ Laura Friel, “UDR Men Acted as Covert British Death Squad,” An Phoblacht, 25 February 1999 Edition.

14 David McKittrick, Seamus Kelters, Brian Feeney, Chris Thornton, and David McVea, Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children Who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles (Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 1999), p. 562.

¹⁵ Fred Holroyd, War Without Honour (Medium: London, 1989), p. 76.

¹⁶ Raymond Murray, The SAS in Ireland (Mercier Press: Dublin, 1990), p. 127.

¹⁷ David McKittrick et al., Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles (Mainstream Publishing, 1999), p. 511.

¹⁸ Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Dublin and Monaghan Bombings, Houses of the Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights (2004), p. 135.

¹⁹ Alistair Kerr, Betrayal: The Murder of Robert Nairac GC (2015), p. 405.

²⁰ Alistair Kerr, Betrayal: The Murder of Robert Nairac GC (2015), p. 30.

²¹ Martin Dillon, The Dirty War (Arrow Books, 1991), p. 169.

²² The Hunt for Captain Nairac, Spotlight Special, BBC One, 19 June 2007.

²³ UTV News, Army soldiers 'witnessed' abduction of Robert Nairac from outside Co Armagh pub in 1977, 27 August 2024. https://www.itv.com/news/utv/2024-08-27/army-witnessed-grenedier-guards-abduction-by-ira

²⁴ The Hunt for Captain Nairac, Spotlight Special, BBC One, broadcast 19 June 2007.