Ambush at Loughgall: The Inside Story

Inside the 1987 SAS Massacre of the East Tyrone Brigade’s ‘A-Team’.

On a spring evening in 1987, eight members of one of the IRA’s most formidable rural units were cut down in a British Army ambush in Loughgall, County Armagh. It was the single deadliest day for the IRA during the post-partition conflict colloquially known as “the Troubles”—a turning point in what republicans called the long war against British rule in the North.

This article is updated periodically.

Last edited: 29 May 2025

Nearly four decades later, the ambush that wiped out the East Tyrone Brigade’s elite unit remains cloaked in secrecy, with repeated attempts by the British state to block a public inquiry. How British forces acquired such precise operational intelligence is still the subject of unanswered questions—and deep suspicion within Republican circles.

The deaths of the eight Volunteers marked more than a tactical defeat. It was the destruction of a unit widely seen as the cutting edge of rural republican militancy. With them died not only lives, but an entire strategic vision—one that had sought to escalate the armed struggle into a full-scale guerrilla campaign across the border counties.

Loughgall was a psychological and strategic watershed: a precision killing that sent shockwaves through the IRA, traumatised its support base throughout Ireland and further afield, and—some argue—paved the way for the political project that would eventually supplant the armed campaign.

Tyrone: A History of Resistance

Tyrone has long held a central—if often understated—place in the tradition of Irish republican resistance. A county scarred by the Plantation and the legacy of colonial land seizure, its hills, valleys, and borderlands have bred generations of quiet defiance that occasionally erupted into open rebellion.

From the days of the United Irishmen and the agrarian Ribbonmen, through to the IRA’s Border Campaign in the 1950s, Tyrone’s republican tradition has been shaped by its geography: rural, close to the border, and marked by a hardline nationalist identity in strongholds like Carrickmore, Galbally, and Pomeroy. The county was the birthplace of Tom Clarke, veteran of the 1916 Rising, and the ancestral home of Seán Mac Diarmada. Even during the quieter decades of the 20th century, Tyrone remained fertile ground for republican organising.

A defining moment in the county’s modern republican history came in the 1950s with the emergence of Saor Uladh (“Free Ulster”), a breakaway militant group formed by Liam Kelly, a former IRA Volunteer from Pomeroy. Disillusioned with the IRA leadership’s caution, Kelly launched his own cross-border campaign against British targets. Though short-lived and limited in scale, Saor Uladh helped embed a tradition of uncompromising militancy in Mid-Ulster—an ethos that would echo decades later in the formation and conduct of the Provisional IRA’s East Tyrone Brigade. That continuity was not only ideological but familial: Liam Kelly was the uncle of Patrick Kelly, the Brigade commander who would later lead the fatal IRA operation at Loughgall.

When the Provisional IRA was formed in 1969, Tyrone was not initially central to its operations. That would change. The 1981 hunger strikes transformed the political climate in the North—and in Tyrone especially, where Martin Hurson, a native of Galbally, died after 46 days without food. His death galvanised local communities and inspired a generation of young men to join the IRA—many of whom would go on to serve in the same unit that was later wiped out at Loughgall.

By the mid-1980s, Tyrone had become one of the most militarised counties in the North, and the East Tyrone Brigade—under the leadership of men like Patrick Kelly, and Pádraig McKearney and Jim Lynagh from Monaghan—had turned the county into a laboratory for rural guerrilla warfare, aimed at undermining British control, one RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) station at a time.

The Conflict in the North of Ireland During the 1980s

By the 1980s, the conflict in the North of Ireland had entered a new and more brutal phase—shaped by the fallout from the hunger strikes, the rise of Sinn Féin as a political force, and an intensifying confrontation between the IRA and the British state.

The decade began in the shadow of the 1981 hunger strikes, during which ten republican prisoners died in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh. Their sacrifice galvanised nationalist communities, drew thousands into open support for the IRA, and radically boosted Sinn Féin’s political credibility. The election of Bobby Sands as MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone while on hunger strike starkly exposed the contradiction at the heart of Britain’s democratic claims in the North.

This political momentum gave rise to a new dual-track strategy known as the “Armalite and ballot box” approach—a combination of armed struggle and electoral intervention. While Sinn Féin contested elections and gained ground, the IRA intensified its military campaign, targeting British soldiers, RUC personnel, UDR members, and key political and economic infrastructure. The goal was to make the occupation unworkable, to erode public confidence in British control, and to apply pressure for eventual withdrawal.

But the British state, too, was adapting. Under Margaret Thatcher’s government, a far more aggressive counter-insurgency doctrine took shape—one that combined military force with deep surveillance, intelligence penetration, criminalisation, and psychological warfare. The Special Air Service (SAS) was deployed in growing numbers in border counties, often operating under a lethal shoot-to-kill policy, while MI5 and the RUC Special Branch intensified efforts to infiltrate, monitor, and disrupt IRA units from within.

In this shifting landscape, rural areas like South Armagh, Fermanagh, and Tyrone emerged as key theatres of IRA activity. Among them, the East Tyrone Brigade stood out as one of the most aggressive and operationally sophisticated. The Brigade was responsible for a string of high-impact attacks on RUC barracks, British patrols, and local contractors seen as collaborators. British intelligence increasingly viewed East Tyrone not just as a threat—but as a strategic challenge to the viability of British control in the rural North.

Meanwhile, loyalist paramilitaries—chiefly the UVF and UDA—continued a campaign of sectarian violence, frequently targeting Catholic civilians, Sinn Féin members, and the families of known republicans. Many of these attacks were carried out with the tacit or active cooperation of the British security forces. In Mid-Ulster especially, patterns of collusion between loyalist gunmen and elements within the RUC and British Army intelligence became increasingly difficult to deny.

Within the IRA itself, strategic tensions were mounting. A growing faction—centred around Gerry Adams and the Belfast leadership—was steering the movement toward a long-term political strategy. Others, particularly in active brigades like Tyrone and Armagh, remained fully committed to the long war. For these Volunteers, the war was not leverage for negotiation; it was the path to a decisive military victory.

It was in this context—of deepening political divisions, sharpened military repression, and rising republican confidence—that the Loughgall ambush would unfold. For many republicans, it would come to symbolise not only the brutal effectiveness of Britain’s counter-insurgency killing machine, but the vulnerability of a bold and uncompromising strand of IRA strategy.

The IRA’s East Tyrone Brigade

By the mid-1980s, the East Tyrone Brigade of the Provisional IRA had emerged as one of the organisation’s most capable, committed, and ideologically driven fighting forces. Rooted in tight-knit nationalist communities and shaped by generational memory, the brigade was both a product of place and a vanguard of revolutionary ambition—combining local knowledge with strategic innovation. While the British state saw it as a threat to regional stability, to many republicans the East Tyrone Brigade represented the most advanced expression of rural guerrilla warfare since the Tan War.

Tyrone’s geography—rugged, rural, and bordering both Monaghan and Armagh—was ideally suited to the development of a low-intensity insurgency. The county’s tradition of republican activity long predated the current conflict, reaching back to the Ribbonmen, the IRA of 1919–21, and the short-lived but symbolically potent Saor Uladh movement of the 1950s. The brigade’s core support was concentrated in strongly nationalist parishes like Galbally, Cappagh, Carrickmore, and Pomeroy, where memory of British injustice, community solidarity, and post-1981 radicalisation created fertile ground for secrecy and recruitment.

Many of the brigade’s Volunteers were young men radicalised by the 1981 hunger strikes, particularly the death of Martin Hurson, a native of Galbally who died after 46 days on hunger strike in Long Kesh. His martyrdom resonated deeply across Tyrone and inspired a new generation of republicans—young, politicised, and prepared to die for the cause of Irish unity.

At the helm of the brigade was Patrick Kelly, a respected and soft-spoken commander from Cappagh, who had risen through the ranks by the early 1980s. Kelly was more than a field officer—he served as a bridge between local units and the IRA’s General Headquarters (GHQ). His leadership was marked by discipline, composure, and a clear commitment to escalating the armed campaign in Mid-Ulster.

The brigade’s ideological direction, however, was shaped most forcefully by Jim Lynagh and Pádraig McKearney. Both had emerged as two of the most ideologically committed and strategically ambitious figures within the Provisional IRA. The men were shaped by prison, hardened by war, and united by a vision that sought not merely to resist British rule in the North—but to systematically dismantle it through a renewed campaign of rural guerrilla warfare.

Jim Lynagh, born in 1956 in Tully, County Monaghan, was one of fourteen children. Unlike many of his comrades, he did not come from a deeply republican background. His entry into the IRA in the early 1970s appears to have been the result of personal conviction, shaped by the political climate of the time and later intensified by his experience in prison. He quickly developed a reputation for fearlessness and tactical aggression.

In 1973, Lynagh was severely injured when a bomb he was carrying exploded prematurely. He survived the blast, was arrested, and later sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment. He served time in Long Kesh, where he became further radicalised and came into contact with some of the movement’s senior republican prisoners. Lynagh immersed himself in revolutionary theory. Within the H-Blocks, he studied the writings of Mao Zedong, Vo Nguyen Giap, and Che Guevara, alongside the history of the IRA’s flying columns during the War of Independence.

He was released in 1978, after serving around five years and in 1979 was elected as a Sinn Féin councillor for Monaghan Urban District Council.

On release, Lynagh immediately re-joined the armed campaign—this time with the East Tyrone Brigade. He brought not only battlefield experience but a strategic doctrine forged in prison, shaped by Maoist guerrilla theory and the tactics of the IRA’s War of Independence. He envisioned the creation of “liberated zones”, starting with isolated police barracks and extending to civil administration, where British presence could be removed through military pressure and republican control asserted.

For Lynagh, electoral politics were never a substitute for armed struggle. He viewed his council seat not as a platform for reform, but as a means of reinforcing and legitimising the military campaign. In his strategic thinking, the RUC barracks, courthouse, and army base were not just targets—they were symbols of British sovereignty to be physically removed. His vision was total: to transform rural Ulster into a network of liberated zones, cleared of Crown forces and defended by guerrilla initiative.

By the early 1980s, Jim Lynagh had acquired a fearsome reputation—dubbed “The Executioner” by the RUC and British intelligence, following a highly symbolic assault in January 1981 on a 230-year-old mansion, Tynan Abbey, owned by one of Ulster unionism’s most prominent families.

The residence was home to Sir Norman Stronge, then 86 years old, and his son James Stronge, both of whom were shot dead during the attack. Sir Norman had been the Speaker of the Stormont Parliament and a long-serving unionist figure, while James, a former Grenadier Guards officer who became an RUC reserve constable, was an Ulster Unionist MP who had succeeded his father.

The IRA unit, reportedly led by Jim Lynagh, entered the abbey and executed both men in what was widely understood—both within the republican movement and in RUC circles—as a deliberate act of political retaliation. The operation was a pre-planned execution of two men considered symbols of the unionist establishment. After the killings, the IRA unit set the house ablaze, destroying the building.

In the aftermath of the Tynan Abbey attack, details emerged of the IRA’s dramatic encounter with responding RUC officers. According to a UDR officer cited in Jonathan Trigg’s book, Death in the Fields, a single RUC vehicle—an armoured Ford Cortina—arrived at the estate's gate lodge and was initially caught off guard when two cars emerged from the Abbey grounds. From these vehicles stepped men in military-style uniforms and combat gear, leading the RUC to briefly hesitate, uncertain whether they were looking at undercover soldiers.

That hesitation was short-lived. As the officer recalled, “there was nothing they could do but just sit there and take it. The IRA team were all over the Cortina.” The Volunteers attempted to fire into the vehicle by wedging a gun between the door and the doorjamb, but couldn’t. While the Cortina's windows were bulletproof, its roof was not armoured—a vulnerability the IRA seemed unaware of. “It was pure luck they survived,” the officer concluded.

Years later, a former RUC officer recounted to a British Army lieutenant how Jim Lynagh himself had jumped onto the bonnet of the RUC car, standing in plain sight as he opened fire directly into the front windscreen. “The fellas in the car were terrified,” the officer remembered. “But the bullet-proof glass held out, thank God.”

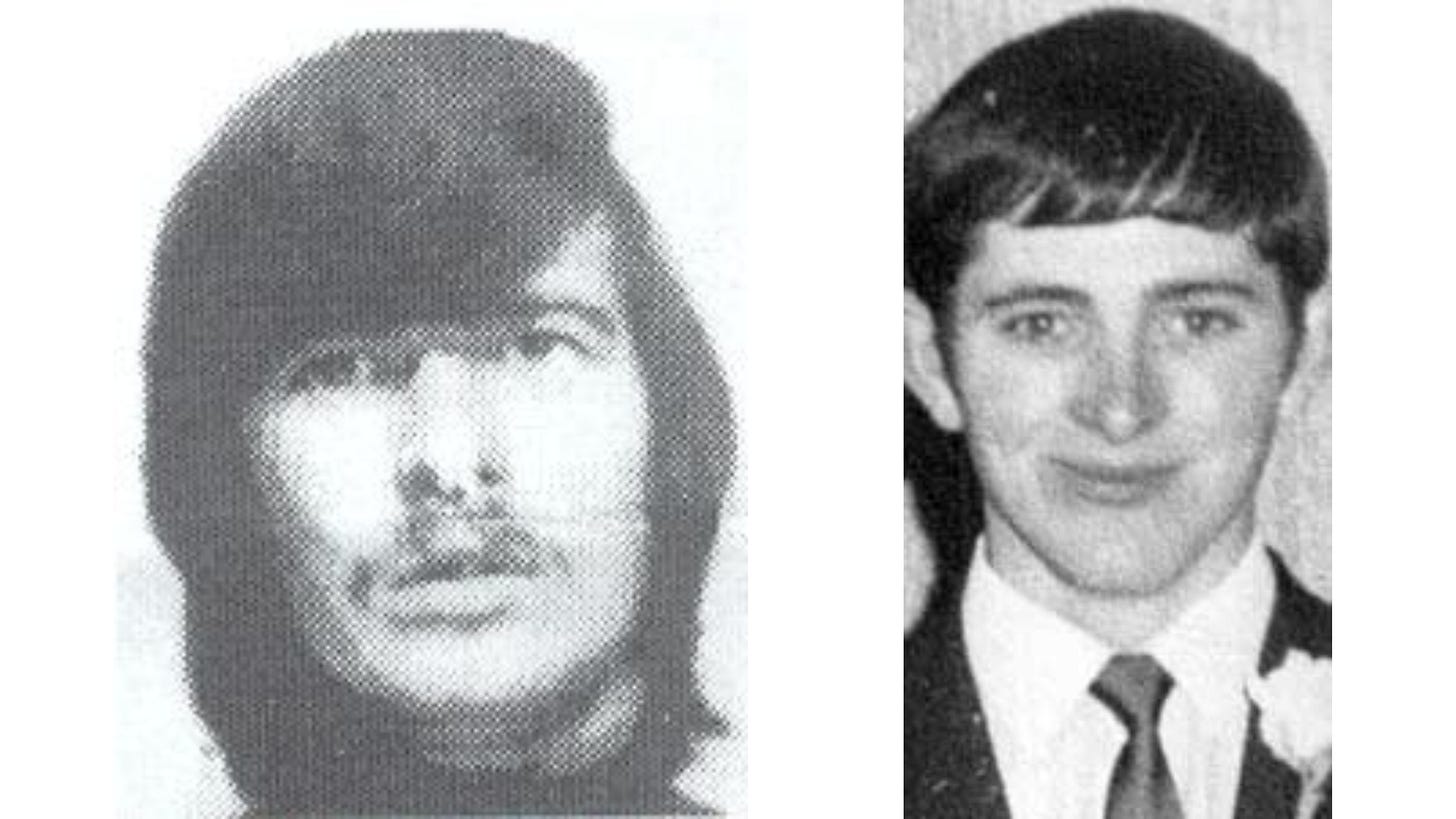

Padraig McKearney, from The Moy, was a H-Block Prison escapee and a battle-hardened republican from a deeply involved family. His brother, Seán McKearney, had been killed in 1974 in a premature explosion along with his comrade, Eugene Martin. Pádraig had joined the IRA in the early 1970s and was arrested in 1977. Like Lynagh, he was politicised in prison and participated in the 1983 Maze escape—the largest prison break in British history—before returning to active service. Quiet and focused, McKearney brought discipline and tactical coherence to the brigade’s operations and shared Lynagh’s belief that the war could be won militarily if properly escalated.

Together, this leadership core gave the East Tyrone Brigade its defining character: tactically aggressive, strategically coherent, and increasingly at odds with the political evolution of the movement’s leadership.

While Lynagh offered revolutionary vision and ideological leadership, McKearney ensured military cohesion and operational discipline. Together, they were a potent combination—men who believed that the IRA campaign had become too fragmented and reactive, and who sought to escalate the war through structure, symbolism, and sustained pressure.

Between 1985 and 1987, the brigade launched a series of tightly coordinated attacks that marked a clear shift in IRA military capability. These included:

The destruction of Ballygawley RUC station in December 1985

The bombing of The Birches RUC station in August 1986 using a digger with a 200lb bomb—a dry run for Loughgall

Attacks on UDR patrols, British military vehicles, and contractors assisting British forces

These operations reflected a mix of engineering ingenuity and tactical evolution. The use of hijacked construction equipment to deliver large bombs was both symbolically audacious and militarily effective. East Tyrone's ASUs were tightly organised, often operating across the Monaghan border—using the frontier not just for refuge, but as part of a broader operational theatre.

Although officially under Northern Command, the East Tyrone Brigade increasingly functioned as a semi-autonomous unit. According to Ed Moloney’s Secret History of the IRA, the Brigade’s leadership had a tense relationship with GHQ, especially with Kevin McKenna, the IRA’s Chief of Staff and himself a Tyrone man. Lynagh and McKearney openly challenged GHQ strategy at internal meetings, and were even said to have discussed forming a more radical military faction if the leadership continued to soften its position.

At the heart of this divide was a fundamental difference in vision. GHQ was leaning more heavily into the “ballot box and Armalite” dual strategy promoted by Adams and McGuinness, while East Tyrone believed that military victory in the border counties was still possible—if ruthlessly pursued. Their proposal to form a flying column—a permanent, mobile guerrilla unit based in the South—was rejected by GHQ as too risky and logistically unsound.

Still, the brigade pressed on with increasing daring and momentum. For many republicans in the area, it felt as though East Tyrone was not just carrying out operations—it was setting the pace of the war.

British military and intelligence services regarded the brigade as a uniquely dangerous threat. Unlike urban ASUs, East Tyrone’s units were deeply embedded in the rural landscape, often made up of close-knit men from the same villages or extended families. Their operations were not haphazard—they were part of a strategic framework aimed at displacing British control from the ground up.

By 1986, the British response was escalating. The SAS, RUC Special Branch, and MI5 had all begun to refocus resources on dismantling the brigade. Surveillance intensified. Informers were sought. Electronic tracking systems were deployed. But the objective was no longer just to disrupt. A long-term plan was taking shape: to eliminate the leadership and ideological backbone of East Tyrone’s campaign. That plan would reach its conclusion in May 1987, in the village of Loughgall.

Patrick Kelly & the IRA’s East Tyrone Command

At the operational centre of the IRA’s East Tyrone Brigade stood Patrick Kelly, a seasoned and respected Volunteer from Cappagh, County Tyrone. Born in 1957, Kelly joined the IRA in his teens—part of a generation drawn into the armed struggle amid the escalating repression and sectarian violence of the early 1970s. Over the following decade, he rose steadily through the ranks and by the mid-1980s had become Officer Commanding (OC) of the East Tyrone Brigade.

By the time of the Loughgall operation, Kelly was regarded as a quiet, serious-minded leader—disciplined, politically aware, and deeply committed to the war effort. His style was one of calm authority. Unlike more ideological figures around him, Kelly rarely engaged in public or doctrinal debate. He was respected among Volunteers not only as a commander, but as a peer—someone who had earned his role through long experience and by leading from the front.

Kelly’s republican lineage ran deep. His uncle, Liam Kelly, had founded the breakaway militant group Saor Uladh in the 1950s and was later elected to Seanad Éireann. Saor Uladh had envisioned a rural insurgency to drive British forces from the North—an idea that would echo decades later in the strategy Kelly helped lead. That continuity, both familial and ideological, reinforced Kelly’s place within a distinct Mid-Ulster tradition of militant republicanism: pragmatic, rural, and uncompromising.

Though not seen as a political firebrand, Kelly was closely aligned with the strategic thinking of Jim Lynagh and Pádraig McKearney. He respected their vision and provided the command structure through which their ideas could be tested and operationalised. Under his leadership, the East Tyrone Brigade evolved into the IRA’s most active and technically sophisticated rural unit, executing a series of high-impact attacks on RUC and British Army positions throughout 1985 and 1986.

Kelly’s role required more than tactical planning. He had to balance multiple demands: managing logistics and weapons caches, coordinating tightly disciplined ASUs, liaising with IRA GHQ, and maintaining morale under the constant threat of surveillance and assassination. He was said to possess emotional intelligence as much as military instinct—able to navigate the often-fraught terrain between a militant field unit and a political leadership growing more cautious.

Though not opposed to Sinn Féin’s electoral rise, Kelly believed that armed struggle remained indispensable. Political gains, in his view, were impossible without sustained military pressure. The East Tyrone campaign was not about symbolism—it was about creating real, irreversible losses for the British state, both on the ground and in terms of psychological control over contested areas.

By late 1986, the brigade had earned a reputation as the IRA’s most effective rural fighting force. Kelly himself was viewed by British intelligence as a high-value target: experienced, loyal, and deeply embedded in the community. His ability to unite seasoned operators like McKearney with younger Volunteers radicalised after 1981 gave the brigade both strategic momentum and ideological continuity.

Britain’s Shoot-to-Kill Policy

The ambush at Loughgall did not occur in a vacuum. It was the culmination of a steadily intensifying phase in what the Provisional IRA had come to define as the “long war”—a protracted campaign of armed struggle and political resistance aimed at ending British rule in the North. In the fields, villages, and border parishes of Mid-Ulster, that war was being waged with increasing confidence, precision, and ambition by the East Tyrone Brigade. And the British state, aware of the growing threat, was preparing to respond—not with arrests or negotiation, but with a lethal, shoot-to-kill policy.

The signs had been emerging for several years. From the mid-1970s onward, a pattern of lethal, pre-emptive force emerged in British counter-insurgency policy—particularly through the covert operations of the SAS and RUC Special Branch. In April 1976, Peter Cleary, an unarmed IRA Volunteer, was shot dead by the SAS near Forkhill, South Armagh, after reportedly being arrested and handcuffed. The British claimed he tried to escape; witnesses and republicans alleged he was executed. The following year, in August 1977, Seamus Harvey, an IRA Volunteer, was shot dead by the SAS near Coolderry, South Armagh. The British claimed he was armed and attempting to evade arrest; local witnesses and republican sources disputed the account, describing it as a deliberate ambush.

In November 1982, three unarmed IRA Volunteers—Sean Burns, Eugene Toman, and Gervaise McKerr—were ambushed and killed by the RUC outside Lurgan, their vehicle hit by more than 100 rounds. Days later, Michael Tighe was killed and Martin McCauley wounded by RUC officers at a hay shed in Ballinderry. Both incidents became central to the Stalker Inquiry, which uncovered efforts by the British state to cover up unlawful killings and mislead investigators.

Then, in December 1983, two East Tyrone Volunteers—Colm McGirr and Brian Campbell—were shot dead by an undercover SAS unit near Coalisland. The British claimed the men were intercepted while preparing an ambush on a joint RUC/UDR patrol. Republicans insisted it was a deliberate execution. Though not the first SAS killing, this marked the regiment’s first known operation in East Tyrone—a clear signal that covert British forces were now turning their attention to the brigade at the heart of the rural IRA campaign.

In July 1984, on the anniversary of hunger striker Martin Hurson’s death, IRA Volunteer Willie Price was killed in an SAS ambush while attempting to carry out an incendiary bomb attack on a factory in Ardboe, County Tyrone. The operation ended in a hail of gunfire, and Price’s death became one of the earlier instances of what republicans viewed as Britain’s evolving policy of targeted executions.

In The SAS in Ireland, Raymond Murray records an account of the incident from a Volunteer who survived the ambush:

“...the whole place lit up with gunfire. William Price fell moaning. The other volunteer (accompanying Willie) crawled back through the long grass to the position he had left and made his escape.”

The rate of fire, according to this testimony, was sustained and overwhelming. The shooting, it was said, continued unabated from the moment Price was hit until his comrade had escaped the kill zone. Only then, after a pause of several minutes, was another single shot heard—followed by a final burst of gunfire.

In keeping with a macabre tradition that would resurface after the Loughgall ambush less than three years later, British forces in the North marked Willie Price’s killing with a celebratory cake, decorated with the words “RIP”, his name, and the location of his death. The practice of commemorating the deaths of IRA Volunteers with personalised cakes was revealed by journalist Peter Taylor in a 2000 BBC documentary, based on interviews with former undercover soldiers.

Price’s funeral marked a turning point. From this moment forward, there was a clear and deliberate shift in British policy regarding republican funerals. In an effort to curb the visibility of republican militarism, British authorities sought to deny Volunteers killed on active service the public honours that had traditionally accompanied their burials. These included colour parties, the firing of volleys over coffins, and the placing of berets, gloves, and tricolours atop the casket.

Yet the effect of this militarised approach to funeral policing was the opposite of what British strategists intended. Heavy-handed interventions by the RUC and British Army—including raids on grieving crowds, harassment of mourners, and physical confrontations at graveyards—did not diminish support for the IRA. Instead, they intensified local anger. Far from containing republicanism, the spectacle of riot shields at funerals, and the disruption of long-standing commemorative rituals, only served to further radicalise nationalist communities. For many, these scenes of aggression transformed funerals into recruitment grounds—and helped swell the ranks of the IRA.

In April 1986, Seamus McElwaine, a high-profile IRA Volunteer and H-Block prison escapee, was ambushed and killed by the SAS near Roslea, County Fermanagh. Forensic evidence later suggested McElwaine had been shot while wounded—executed at close range. His killing sparked renewed outrage and reinforced the belief within republican circles that the British state had fully embraced a shoot-to-kill doctrine.

These operations, culminating in the killing of Seamus McElwaine, made clear to many republicans that Britain had abandoned any pretence of arrest or due process when dealing with IRA Volunteers in the field. Instead, lethal force had become policy—a deliberate and institutionalised tactic, not an exception. The ambush at Loughgall, less than a year later, would be the most devastating expression of that policy to date—but it would not be the last. In the years that followed, the shoot-to-kill approach would be deployed repeatedly, in Coagh, Clonoe, and elsewhere, often with the same clinical precision and controversial aftermath. Loughgall did not mark the beginning of this policy—it marked its escalation.

East Tyrone and IRA’s Long War

By the early 1980s, the Provisional IRA had embraced a doctrine it called the long war—a protracted campaign of armed resistance, attritional pressure, and parallel political engagement aimed at ending British rule in the North. While urban centres like Belfast and Derry remained active, it was in the rural border counties—Tyrone, Armagh, and Fermanagh—where the war took on a different shape. Here, geography, tradition, and community solidarity allowed the IRA to wage a form of low-intensity insurgency that was difficult to monitor and even harder to suppress.

In this context, East Tyrone—with its tight-knit republican heartlands in Galbally, Cappagh, and Carrickmore—became one of the most active and dangerous operational zones for British forces.

The brigade conducted a series of increasingly audacious and coordinated attacks, not only to inflict casualties but to undermine the British presence structurally and symbolically.

Notable among these was a landmine ambush at Ballygawley in July 1983, where a British Army convoy of five Land Rovers was hit by a 300 kg culvert bomb. The explosion left a crater 40 feet wide and 15 feet deep, killing four soldiers. The Irish Times later observed:

"This stretch of road has been a favourite ambush spot for successive generations of IRA men since the 1920s. In 1920 a number of police ‘specials’ were killed in an IRA ambush there. In March 1973 a British army lieutenant was killed when his armoured car was blown up by a similar 500 lb landmine along the same road."

On 25 September 1983, Pádraig McKearney was among the 38 republican prisoners who took part in the dramatic escape from Long Kesh, the largest prison breakout in British and Irish history. By early 1984, he had rejoined active service in East Tyrone, aligning once again with the Provisional IRA’s local brigade. McKearney began to advocate for what he termed the movement’s “third phase” of armed struggle—a strategy of strategic defence, whereby repeated attacks on RUC, UDR, and British Army installations would render certain areas ungovernable. The ultimate goal was to deny Crown forces any viable foothold in republican strongholds through sustained, localised attrition.

Among the most ambitious and controversial ideas to emerge from within the IRA during the 1980s was a proposal developed by Jim Lynagh and Pádraig McKearney—two Volunteers who combined battlefield experience with revolutionary conviction. Determined to break the stalemate of guerrilla attrition, they devised a plan for a permanent, full-time flying column that would shift the war onto new terrain—literally and strategically. The two men began formulating a strategy that would escalate the conflict into what they called a “total war”

This vision wasn’t just a tactical refinement; it represented a radical departure from the IRA’s conventional tight-knit ASUs. Their proposal called for a self-contained guerrilla unit of 20 to 30 highly trusted Volunteers, based in the South, far from the surveillance-heavy zones of British-controlled territory. There, the unit would live, train, and strike from a position of mobility and secrecy—modelled on the flying columns of the War of Independence, but adapted for modern conditions.

The concept took inspiration from the IRA’s original flying columns of the 1919–21 War of Independence, particularly in Cork and Munster, where small, mobile units had successfully harried British forces and withdrawn to the countryside. But Lynagh and McKearney envisioned a modernised, more secure version.

Lynagh and McKearney drew inspiration not only from the flying columns of the 1920s or the Vietnamese guerrillas who wore down American forces in a grinding war of attrition. Closer to home, they looked to the South Armagh Brigade, which had, through a persistent campaign of ambushes, landmines, and remote-controlled roadside bombs, effectively established a liberated zone. In South Armagh, the British military was largely denied use of the region’s web of country roads, forced instead to rely on helicopter transport to avoid the ever-present threat of IEDs. The once-picturesque landscape became a theatre of occupation: dotted with steel watchtowers, ringed with fortified bases, and constantly buzzing with the sound of helicopters ferrying troops and supplies—unable to move by land.

Lynagh and McKearney’s proposed unit would consist of 20–30 trusted Volunteers, based at a remote and well-protected training camp in the Republic. It would operate semi-independently from local ASUs, and its members would live, train, and move together as a closed, self-reliant team.

Security was key. The flying column would strike three to five times per year, with each operation designed to cause maximum political and psychological damage. The unit would rely on small satellite cells to gather intelligence and monitor targets, but the column itself would remain in deep concealment. If a member turned informer, he would have to physically separate from the group in order to communicate with handlers—a difficult and risky proposition. In this way, the strategy aimed to neutralise the growing threat of infiltration that plagued many local units.

For Lynagh and McKearney, the column was not merely a tactical adjustment—it was a strategic shift. They rejected what they saw as GHQ’s flawed reliance on steady attrition and military pressure designed to support Sinn Féin’s political advance. They did not believe that “sending Brits home in boxes” would win the war. Instead, they advocated for a sustained offensive to make the British presence unviable, clearing bases, destroying infrastructure, and forcing Crown forces to retreat from rural areas—creating “liberated zones” where the state could no longer function.

The proposal was brought directly to IRA Chief of Staff Kevin McKenna, but it was rejected—deemed too ambitious, too logistically complex, and too risky. McKenna also denied their request for a dedicated training camp. But key elements of that doctrine were already being implemented in East Tyrone.

In 1985, Patrick Kelly became Officer Commanding (OC) of the East Tyrone Brigade. Under his leadership, the unit evolved into one of the IRA’s most formidable and disciplined formations. Its Active Service Units (ASUs) were composed of young, highly trained Volunteers—many from long standing republican families, and many radicalised by the 1981 hunger strikes.

Under the leadership of Patrick Kelly, the East Tyrone Brigade evolved into a well-organised, technically adept, and ideologically confident fighting unit. Its Active Service Units (ASUs) were composed of highly committed Volunteers—many of them second-generation republicans, and many radicalised by the 1981 hunger strikes. For them, this was not simply a continuation of past conflicts—it was a new war with modern tools, bigger ambitions, and deeper roots.

Between January 1984 and the end of 1986, the IRA intensified its offensive across the North, launching over seventy attacks on RUC installations and killing more than thirty-five police officers. Among the deadliest of these operations was the February 1985 mortar assault on Newry RUC station, which claimed the lives of nine officers. In its aftermath, the IRA issued a stark warning: any contractors who assisted in rebuilding damaged police infrastructure would themselves become targets.

By this time, the East Tyrone Brigade had concluded that the roughly two dozen RUC stations scattered across rural Tyrone were increasingly vulnerable. Most were isolated, lightly staffed, and poorly defended—ideal targets for a campaign of sustained disruption. The brigade set about identifying and attacking these installations, combining local intelligence with escalating technical and operational capability.

Among those directing this campaign was Pádraig McKearney, whom the Republican Movement later described as “a key figure on some of the most daring and innovative missions in recent years.” To British security forces, he was one of the most seasoned and dangerous guerrilla operators in the North.

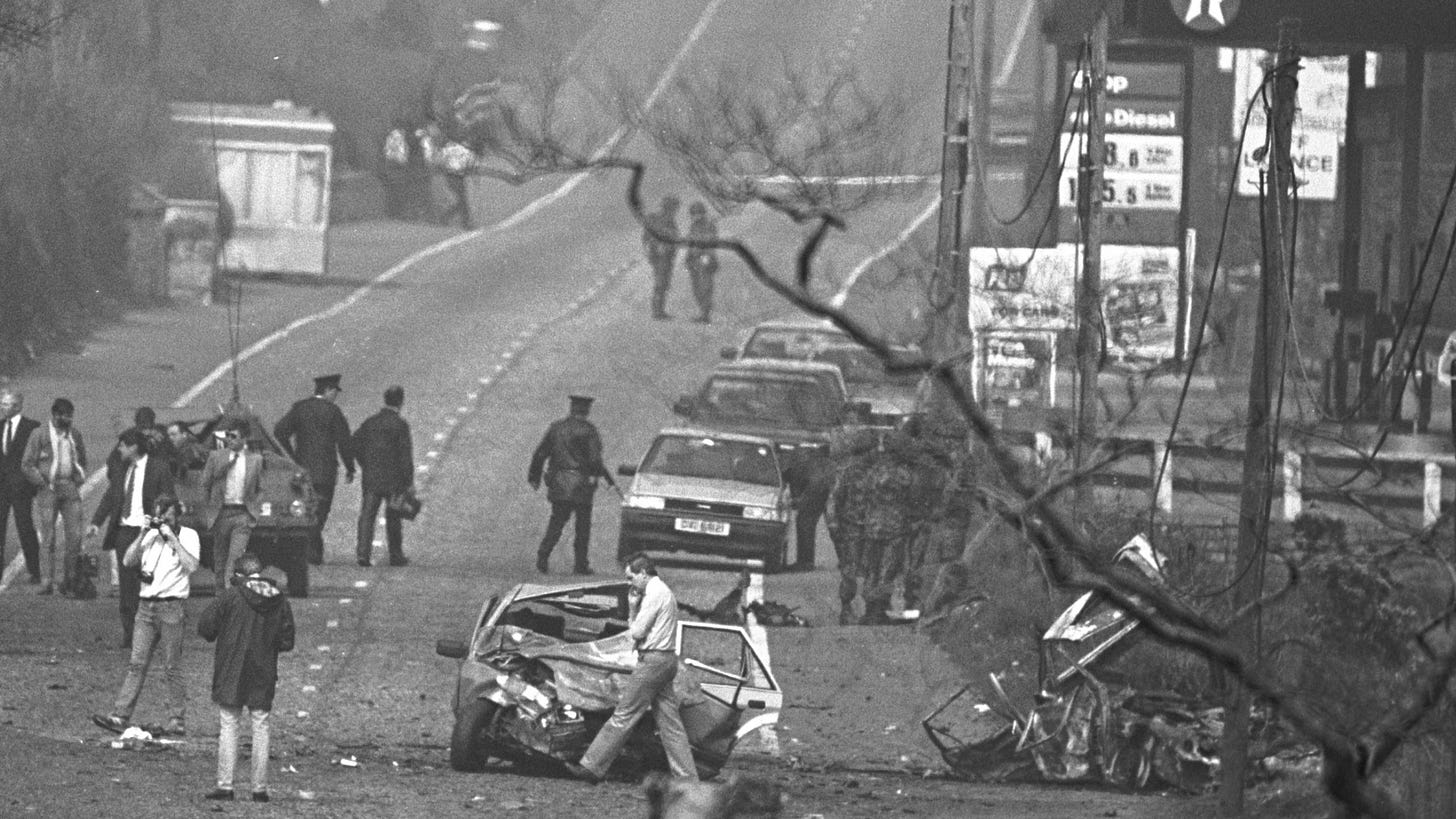

The assault on Ballygawley police station on 7th December 1985 was one of the East Tyrone Brigade's most sophisticated and successful attacks up to that point, and it served as a prototype for future frontal assaults on RUC stations.

The operation unfolded just before 7 p.m., as RUC officers were preparing to end their shift. The IRA launched a coordinated gun and bomb attack using a carefully assembled Active Service Unit. The attackers opened fire with automatic weapons at the front of the station, killing two RUC officers—Constable George Gilliland (34) and Reserve Constable William Clements (52). The Irish republican magazine IRIS described the attack:

“One volunteer took up a position close to the front gate. Two RUC men opened the gate and the volunteer calmly stepped forward, shooting them both dead at point blank range. Volunteers firing AK-47 and Armalite rifles moved into the barracks, raking it with gunfire.”

After neutralising the front, the Volunteers entered the building, seized documents and weapons, and planted a 50kg bomb—contained in a beer keg—at the entrance. The bomb devastated the station.

Three other terrified RUC officers managed to escape through the back during the chaos. “Alan,” an RUC officer who was present during the Ballygawley attack, later recalled the scene in Peter Taylor’s Provos:

“The whole place just erupted. The blast lifted me and threw me into a wall about fifteen feet in front. I had great difficulty trying to breathe because all the air had been sucked out of me. I was gasping for breath and couldn’t hear anything. The explosion had deafened me. The explosion had taken out the electricity supply so the whole place – and the whole of Ballygawley – was in darkness. I climbed out of the rubble and made my way up to the front gate. Lying there was Billy Clements. I lifted his head up to see if I could feel a pulse in his neck but he was dead. Then we found George, covered in rubble. He was dead too. Both of them must have been cut down by the automatic fire in the early stages of the attack. I tried to hold myself together so that I wasn’t physically sick and tried not to break down because I knew there was still work to do. You’ve just got to keep going.”

The scale of Pádraig McKearney’s operational activity became clearer in the aftermath of the Loughgall ambush, when forensic teams examined the eight weapons recovered from the scene. These firearms were linked to over thirty separate incidents. One in particular—a .357 Ruger revolver—was traced to six shootings. It had originally been taken during the Ballygawley police station attack, seized from the body of Reserve Constable William Clements. According to security sources, the weapon later became McKearney’s personal sidearm. It was subsequently used in the killing of John Kyle, a civilian from the Omagh area whom the IRA accused of supplying construction materials to aid in the repair of RUC installations.

The attack on Ballygawley RUC station dealt a sharp blow to British authority and significantly boosted morale within the IRA—particularly among the East Tyrone Brigade, who saw themselves as modern-day heirs to the flying columns of the 1920s or the Vietnamese guerrillas who had outlasted Western armies.

Just four days later, on 11 December 1985, the East Tyrone Brigade carried out another major operation—one often overshadowed by the earlier Ballygawley attack and the later Loughgall ambush. In a devastating mortar strike, the IRA destroyed the RUC station at Tynan, scoring a direct hit on the compound. A total of four large-calibre Mark 10 mortars, each reportedly packed with up to 100 kg of explosives, were launched. The blasts tore through the station—shielded behind a high steel fence—reducing it to rubble and craters and gutting the building in a raging fire “that could be seen from miles around,” according to a BBC report. Four RUC officers were injured.

Ironically, the mortars were launched from a blue Toyota HiAce van—the same model and colour later used in the Loughgall operation. A rectangular opening had been cut into the roof, allowing a single IRA Volunteer to fire the mortars from a concealed position inside the vehicle. According to the BBC, the assault on Tynan marked “the fourth attack on an RUC station in the last week”—a clear sign of escalating tempo and a grim prelude to the operation at Loughgall.

Eight days later, at 7 p.m. on 19 December 1985, another RUC station—this time in Castlederg, near the border—was wrecked by a mortar barrage. Six people were injured in the attack, including an RUC officer. The IRA fired six shells, once again using a stolen van modified with a hole cut through its roof to launch the salvo toward the station.

Three days after the Castlederg mortar attack, the East Tyrone Brigade struck again—this time launching a barrage of seven mortars at the joint British Army and RUC base in Carrickmore. The escalation in attacks on RUC installations across the Six Counties was becoming unmistakable. A BBC news report, covering the mounting campaign, noted that RUC staff had begun demanding concrete buildings to replace the wooden structures being routinely decimated by IRA mortar fire.

On 13 January 1986, the IRA’s East Tyrone Brigade, in their second attack on Carrickmore RUC and British army base, fired another Mark 10 mortar. The improvised device was set up in a nearby field, with the projectile launched over a residential home before landing in the centre of the RUC base compound. The explosion caused extensive structural damage and injured a British soldier.

A confidential memo issued by the Department of the Taoiseach in the Republic hints at the growing strategic impact of the IRA’s mortar campaign—particularly in County Tyrone. The document, focused on security cooperation with the British, noted:

“The main point of interest since the [Anglo-Irish] Agreement has been a series of IRA attacks on RUC officers and outlying RUC stations and military checkpoints. There have been reports of up to 7 mortar attacks. It has been alleged that the mortars were made in the South.”

The IRA in Tyrone became adept not only at launching mortar attacks but also at executing highly effective undercar booby trap operations. One such attack occurred on the night of January 15, 1986, when eighteen-year-old Victor Foster, a part-time member of the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), was killed by a Provisional IRA bomb in the Spamount area near Castlederg, County Tyrone. The device—ingeniously concealed in his car and triggered by a mercury tilt switch—detonated roughly 100 yards from his home in Gamble Park, just moments after he had set off with his fiancée. She survived the blast but was left permanently maimed, losing the sight in one eye. The targeting of Foster, so close to home and while off-duty, underscored the IRA’s growing confidence and capability in striking local security force members with precision and psychological impact.

On 1 February 1986, the RUC barracks at Coalisland was devastated by a 300 kg van bomb—one of the most destructive attacks of its kind to date. Just two months later, in April 1986, Jim Lynagh was released from Portlaoise Prison in the Republic. His return to active service would coincide with a new phase of escalation in the East Tyrone Brigade’s campaign—marked by increased technical sophistication, bolder operations, and the emergence of what would later be known as the IRA’s “A-Team.”

The most significant operation of this new phase came on 11th August 1986, when the “A-Team” destroyed the RUC barracks at The Birches in County Armagh. The attack marked a step-change in IRA tactics—combining precision planning, engineering ingenuity, and overwhelming firepower. For many, it was a dry run for Loughgall.

By mid-1986, the East Tyrone Brigade—now under the operational command of Dungannon-based Paddy Kelly—had been refining a new offensive strategy. Their next target was the RUC base at The Birches in County Armagh. The station was surrounded by a high mesh fence, designed to deter rocket and grenade attacks. To overcome this, the IRA devised an innovative assault plan: a mechanical digger would be used to smash through the perimeter, with a large explosive device concealed in its front bucket. The goal was not just to breach the station’s defences, but to demolish it entirely in a single, devastating strike.

The operation at The Birches is believed to have involved over thirty-five IRA members, making it one of the largest coordinated actions ever undertaken by the East Tyrone Brigade. A diversionary team launched a bomb attack in Pomeroy, approximately 30 kilometres from the target, drawing security forces away from the primary objective. With their attention diverted, the main assault unit moved in on the unmanned RUC station at The Birches. The base was levelled by a massive explosion, triggered by the 100 kg bomb concealed in the bucket of the mechanical digger–this would become the blueprint for the Loughgall assault. The IRA unit then escaped by boat across Lough Neagh, successfully avoiding a widespread deployment of RUC and British Army roadblocks and checkpoints.

The mechanical digger used in the Loughgall attack was driven by Declan Arthurs, a young IRA Volunteer who was well accustomed to operating similar machinery on his family farm. Arthurs was routinely targeted by British forces, and in January 1987, he spent nearly the entire month caught in a cycle of arrest, release, and re-arrest. Speaking to journalist and author Peter Taylor, Amelia Arthurs, Declan’s mother, recalled:

“I was very afraid he was going to be killed. That’s what they often told him when they stopped him at checkpoints. One night they made him lie down on the road and measured him and told him they were going to kill him.”

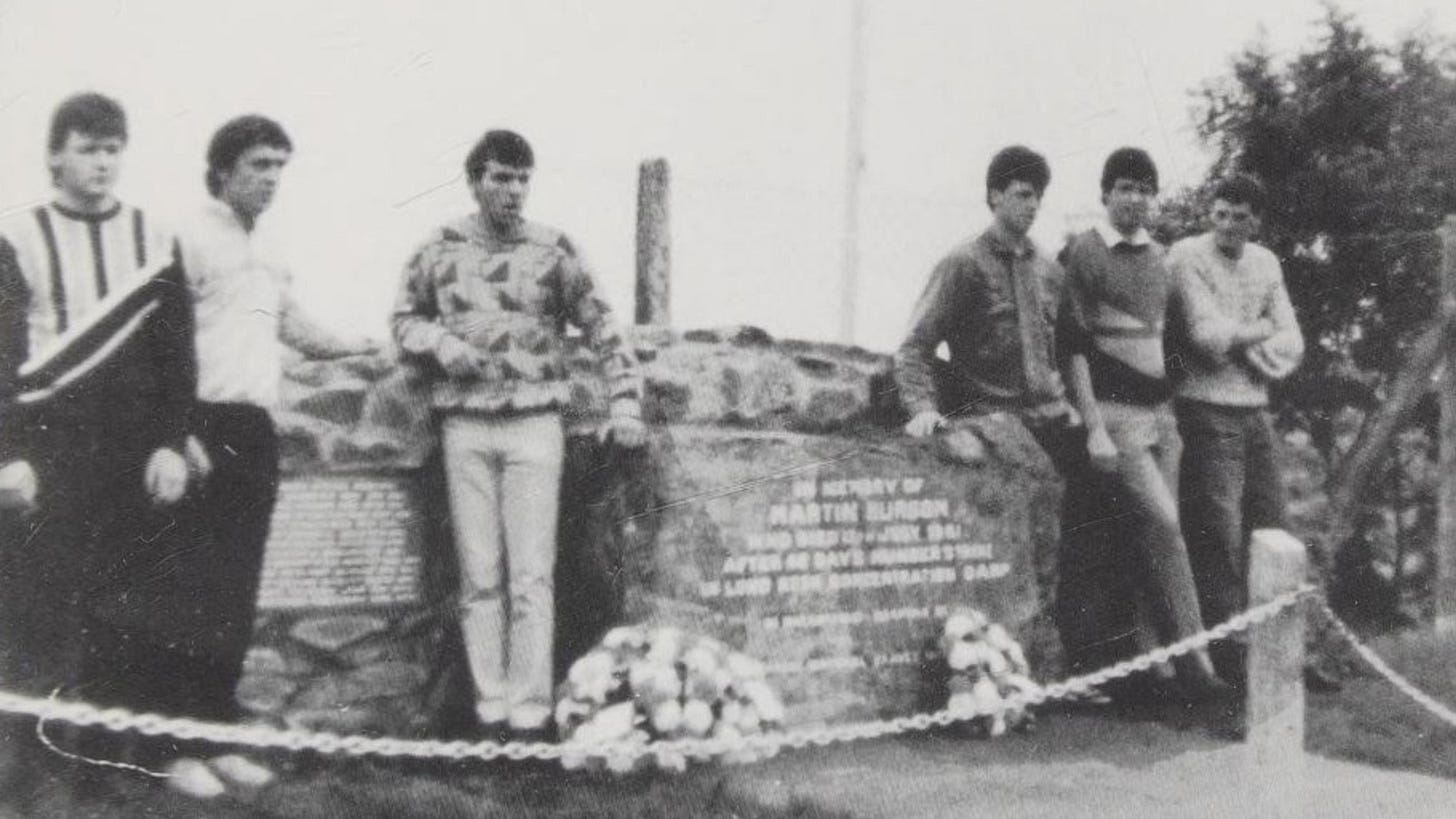

That same year, Declan Arthurs was photographed with his friends and fellow IRA Volunteers at a memorial for Martin Hurson, who had died on hunger strike in July 1981 after 46 days without food, aged just 24. Pictured with Arthurs were Seamus Donnelly, Tony Gormley, and Eugene Kelly, Martin McCaughey and Dermot Quinn—all in their early twenties, and all deeply influenced by the sacrifice of the hunger strikers. Five of the six pictured would die in two separate SAS ambushes, their deaths forming part of that same chain of generational loss and determination.

The East Tyrone Brigade had pioneered the use of digger-delivered bombs, mastered escape routes, and began operating with increasing technical and operational sophistication. The objective was shifting from inflicting casualties to dismantling Crown presence in the borderlands.

The destruction of the RUC station at The Birches was one of the key factors that led to the decision to deploy an additional two British Army battalions to the North of Ireland, reflecting growing alarm within the British security establishment over the IRA’s escalating rural campaign, particularly in East Tyrone.

A member of the British security forces told author Mark Urban of the attack:

"The Birches RUC station was destroyed by the bomb, creating problems for the authorities about how to re-build it. The Tyrone IRA was able to combine practical skills such as bomb-making and the welding needed to make mortars with considerable resources. Its members went on operations carrying the latest assault rifles and often wore body-armour similar to that used by the security forces, giving them protection against pistol or submachine-gun fire. By 1987 they had also succeeded in obtaining night-sights, allowing them to aim weapons or observe their enemy in darkness."

The IRA volunteers weren’t just part-time insurgents; by 1987, the East Tyrone Brigade was operating as a guerrilla force approaching professional grade.

News headlines throughout 1986 continued to detail the routine of IRA roadside bombs, ambushes, booby traps, targeted killings of British security personnel and repeated mortar barrages, including another at Carrickmore RUC station in October.

By the end of 1986, the British security apparatus had taken full notice. Intelligence services—including MI5, RUC Special Branch, and E4A—ramped up surveillance across Tyrone and Armagh. New listening devices were deployed, aerial reconnaissance intensified, and personnel movements were increasingly monitored. Crucially, in the wake of the Anglo-Irish Agreement, cross-border intelligence sharing between British and Irish security forces expanded significantly, providing the British with greater insight into republican activity and movement south of the border. Within this emerging framework, East Tyrone was viewed as the epicentre of a new and dangerous form of rural insurgency—and its senior figures were being closely and systematically tracked.

Throughout 1986 and into 1987, news headlines continued to chart the relentless rhythm of IRA operations: roadside bombs, ambushes, booby traps, and targeted killings of British security personnel—particularly UDR soldiers—as well as repeated mortar barrages, including yet another strike on Carrickmore RUC station in October.

Then, in April 1987, Lord Justice Maurice Gibson and his wife were killed in a border bombing as they crossed into County Down after returning from a holiday abroad. A decade earlier, Gibson had famously acquitted a British soldier who shot dead Majella O’Hare, a 12-year-old girl killed in Whitecross, County Armagh and was widely accused of endorsing the apparent British shoot-to-kill policy after acquitting police officers who shot the three unarmed IRA Volunteers—Sean Burns, Eugene Toman, and Gervaise McKerr in 1982.

Though the bombing was carried out by the IRA’s South Armagh Brigade, not East Tyrone, the killing of such a senior judicial figure shocked the British establishment. Amid escalating IRA activity across the border counties, the pressure on the British military intensified to decapitate the organisation’s most dangerous units—chief among them, the East Tyrone Brigade.

The Next Target: Loughgall RUC Station

By early 1987, IRA leaders in Belfast were pressing for a renewed offensive against hard targets. The success of the South Armagh Brigade, which had largely denied the British military access to its local terrain, set a benchmark for other brigades across the North. The East Tyrone Brigade, known for its operational ambition and tight discipline, was close behind. According to a security source quoted in Jonathan Trigg’s Death in the Fields, “they weren’t too far behind”—a recognition that East Tyrone had become a serious strategic concern for British intelligence.

Against this backdrop, Loughgall RUC station was selected as the next target. Situated in rural County Armagh, the base was seen as vulnerable: lightly staffed, part-time, and located in an area increasingly regarded by the IRA as suitable for “liberated zone” tactics. The attack would follow the model perfected at The Birches—a mechanical digger with a bomb in its bucket would breach the perimeter fence, while an armed unit would provide cover, destroy the station, and withdraw.

What the Volunteers did not know was that, by this point, they were already under surveillance. The SAS, along with RUC Special Branch and other intelligence units, had been monitoring the East Tyrone Brigade for weeks.

In what would later fuel allegations of entrapment and a premeditated shoot-to-kill policy, British forces—according to speculation in Mark Urban’s Big Boys’ Rules—are believed to have made the decision to allow the killing of William Graham, a UDR soldier, in order to protect the broader ambush operation being prepared at Loughgall. This accusation has been repeated by groups representing victims of the IRA.

The trap was now set. The IRA believed it was carrying out a textbook operation—one that would strike another symbolic and strategic blow against the British presence in the North’s rural areas. Instead, they were walking into a carefully prepared killing zone.

“A Massive Ambush”

The operation to intercept the IRA’s “A-Team” had been in motion for days—some say, weeks—before the attack on Loughgall. British intelligence units had been tracking the movements of East Tyrone’s most active Volunteers, monitoring vehicles, gathering surveillance, and waiting for the moment to strike. What followed on 8 May 1987 was not a chance engagement, but a deliberate and meticulously prepared ambush—the deadliest single operation mounted by British forces during the conflict.

Somehow, the British had acquired intelligence indicating that an attack on the rural RUC base at Loughgall was imminent. At the centre of this intelligence-gathering effort was the RUC Tasking and Co-ordinating Group (TCG)—a unit created to enhance operational coordination between the RUC and British Army. Working alongside them was the Mid Ulster detachment of 14 Intelligence Company, known as “the Det”—a covert group of special forces-trained operatives skilled in surveillance, close-target reconnaissance, advanced driving, and armed engagement. Also involved was E4A, a highly secretive arm of the RUC’s Special Branch, tasked with running agents and collecting human intelligence (HUMINT) on republican paramilitary networks. Supporting these intelligence agencies on the ground was the Headquarters Mobile Support Unit (HMSU)—a specialist RUC tactical team trained by the SAS, designed for rapid-response actions and armed interceptions. Together, these units formed the backbone of the British state’s covert war in the North, blending surveillance, informers, agents, and special operations across a complex web of competing and shadowy agencies.

The date of the attack was set for Friday, 8 May 1987. While speculation persists over how the British became aware of the impending IRA operation, it is widely believed that the breakthrough did not come from a single source, but rather from a convergence of intelligence-gathering methods—particularly surveillance and signals intercepts—gradually pieced together by British security forces. Like the IRA in South Armagh, the East Tyrone Brigade was seen as largely impregnable to informers, drawing much of its strength from tight-knit, deeply rooted nationalist communities where external penetration was exceptionally difficult. What emerged instead was a coherent picture of the unit’s intentions, enabling the ambush to be meticulously planned in advance.

In the weeks leading up to the Loughgall ambush, British security forces were already on high alert. The IRA’s campaign had intensified significantly over the previous six months, and pressure was mounting on the British government to respond. Calls for tougher action—particularly from within the right-wing press and former political figures—grew louder following a series of high-profile attacks. On 28 April 1987, newspapers carried provocative headlines: The Daily Mail demanded “Unleash SAS on the killer squads,” while the Daily Mirror declared “SAS set to Swoop.”

Inside the government, momentum was building for a more aggressive strategy. Northern Ireland Secretary Tom King met with senior police and army leadership, including RUC Chief Constable Sir John Hermon and Lieutenant General Sir Robert Pascoe, the British Army’s commander in the North. Just days before the ambush, on 6 May, King outlined a new security package in the House of Commons, promising an increase in RUC reservists and a greater full-time role for the UDR. The following day, Hermon publicly hinted at an expanded role for the SAS, stating that future operations would be “tougher, different, and sharper,” and would involve both “overt and covert” tactics.

It remains unclear whether Hermon’s comments were a calculated signal or coincidental timing. But by then, British forces had already obtained detailed intelligence on the planned IRA attack at Loughgall. Surveillance was active, communications were being monitored, and according to some accounts, a compromising phone call made by an IRA Volunteer was intercepted and passed to the RUC. With pressure from Westminster and demands for retaliation from unionist quarters, the stage was set—not for an arrest operation, but for a deliberate and lethal ambush.

In the days leading up to the Loughgall ambush, several of the IRA’s most seasoned Volunteers had reportedly moved into Tyrone from across the border. Declan Arthurs, absent from his home for some time, was considered effectively “on the run.” Pádraig McKearney, a well-known escapee from Long Kesh, and Jim Lynagh, from Monaghan, would have immediately drawn attention from British intelligence had they crossed north without operational cover. It’s believed the group arrived by Tuesday, 5 May, and were billeted in safe houses in the area.

Planning in the days before the attack would have involved the preparation and delivery of the bomb, as well as the hijacking of a mechanical digger—a tactic previously used to devastating effect at The Birches. IRA OC Patrick Kelly is believed to have passed the operational plan up the chain of command for approval. According to local sources cited by journalist Jim Cusack, as many as 14 men may have played roles in the operation, including the scout cars and a team tasked with detaining the owner of the digger to prevent early detection.

In the lead-up to the attack, IRA engineers constructed the bomb intended for use at Loughgall—a 200 kg semtex-based device, concealed inside an oil barrel. According to reports, E4A, the covert intelligence wing of the RUC’s Special Branch, had been tasked with monitoring the device, possibly for several weeks prior to the operation. The bomb, built in Ardboe, was loaded onto a boat and transported across Lough Neagh to Maghery on the day of the attack—a journey made in secrecy, but evidently not beyond the reach of British surveillance.

The digger—a JCB—was hijacked from the Mackle family farm on Lislasley Road, just outside Moy, on the afternoon of 8 May. Five IRA Volunteers arrived as the family was returning home. Two of them remained behind to detain the family; the others left with the digger and diesel fuel. Declan Arthurs, whose family had an agricultural contracting business, drove the machine. Around 6:30 p.m., the digger left the farm and began its journey toward Loughgall.

Rather than take the direct route, the unit chose a circuitous path, likely to avoid detection and to pick up the explosive device. While the straight-line route was only about four miles, they looped through Portadown, then swung right at Ardress crossroads—nearly doubling the distance. Somewhere along the way, the bomb was placed in the front bucket of the slow-moving and easily-spotted JCB, beneath rubble and brick for concealment. Two forty-second fuses were added.

Meanwhile, a separate Active Service Unit of seven Volunteers travelled toward Loughgall in a blue Toyota HiAce van (registration: GJI 4417). The vehicle had been hijacked by a team of two earlier that afternoon, around 2:30 p.m., from a business premises in Dungannon. The owner was instructed by the Volunteers not to report the van stolen for at least four hours, a tactic intended to delay any potential police alert and help the unit reach its target undetected.

Scout cars, likely linked via radio, provided overwatch and would have issued warnings in the event of roadblocks. The driver of the van was Eugene Kelly, who was intimately familiar with the web of rural roads criss-crossing east Tyrone and north Armagh.

British intelligence, however, was already several steps ahead. Fergal Keane, writing in the Sunday Tribune, later reported that locals had noticed an unusual drop in British patrols beginning on Wednesday, 6 May—a strong indication that the SAS and RUC had already taken up covert positions in the village. The RUC station itself, normally staffed by six officers, had been vacated in advance and replaced by a stake-out team composed of SAS personnel and RUC marksmen positioned strategically around the station.

According to Mark Urban’s Big Boys’ Rules, an elderly local resident walking his dog inadvertently spotted one of the SAS unit’s covert positions in the days leading up to the ambush. Despite the risk of exposure, the decision was made to press ahead with the plan—an operation described by one British officer as a “massive ambush”, now codenamed Operation Judy.

The RUC barracks, located at the far edge of Loughgall village, had long been considered a soft target. Open only four hours each day—9 to 11 a.m. and 5 to 7 p.m.—it closed 20 minutes early on Fridays, meaning that by 6:40 p.m., the IRA would have expected it to be empty. The routine “limited opening hours” policy had been implemented years earlier to protect isolated stations from mortar attacks. On this occasion, however, the closure was part of the trap.

For Operation Judy—the codename for the Loughgall ambush—the British determined that twenty-four SAS troopers would be required. The bulk of the SAS unit was airlifted from Hereford, England—underscoring not only the operation’s priority and scale, but also the importance placed on maintaining secrecy in the lead-up and enforced silence in its aftermath. In total, over fifty personnel—drawn from the SAS, RUC HMSU, and military surveillance units—were deployed, all highly trained in covert observation and close-quarters combat. In addition, hundreds of support troops, including members of the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), were positioned in surrounding areas to seal off the village and reinforce the cordon.

The ambush was carefully choreographed. In the hours leading up to the attack, SAS units were deployed in concealed positions within and around the police station, including the church graveyard and hedgerows overlooking the approach routes. Their placement was calculated to create interlocking fields of fire, ensuring that once the IRA unit arrived, there would be no chance of escape.

Curiously, the SAS personnel tasked with the operation were armed with Heckler & Koch G3 assault rifles—the very same model carried by some members of the IRA team they were targeting. In addition, the ambush force had at least two belt-fed General Purpose Machine Guns (GPMGs), capable of delivering rapid, sustained fire. These were positioned to maximise coverage of the so-called “kill zone” at the front of the station.

The main killing group of SAS operatives was stationed in and around the police station itself, arranged under the direction of a senior Hereford-based commander. This configuration served a dual purpose: to maximise tactical dominance, and to provide a strategic and legal pretext for opening fire on IRA Volunteers who believed they were attacking an unoccupied outpost.

Beyond the kill zone, covert observation teams monitored the surrounding area, while at least two cut-off units were strategically positioned to intercept any IRA Volunteers who might attempt to escape. The entire formation was meticulously designed to trap, encircle, and eliminate the ASU, ensuring there was no viable route of retreat. Members of the cut-off units were reportedly equipped with caltrops—small, multi-spiked area denial weapons intended to puncture tyres and disable vehicles, further reducing the chances of an escape by road.

The ambush was laid out in a triangle-shaped formation, with the kill zone focused at the station’s entrance, where the IRA team was expected to strike. The main SAS contingent was embedded inside the station, along with three RUC officers, while additional fire teams covered the flanks from the church graveyard and a road junction on the hill above. Each location was chosen to allow overlapping fields of fire, ensuring full control over every approach and a swift, overwhelming response once the operation was triggered.

It was around 17°C and partially overcast on the evening of 8 May 1987. The village of Loughgall lay eerily silent. Local residents later recalled that there was no sign of police or military presence, no helicopters overhead—just stillness.

At around 6:00 p.m., the IRA unit began assembling for the operation. Members changed into blue boiler suits, donned body armour, and pulled on balaclavas. Some took additional precautions—wearing surgical gloves and yellow football gloves to avoid leaving forensic evidence such as fingerprints or gunshot residue. But Pádraig McKearney, the veteran Volunteer and 1983 H-Block escapee, refused such measures. Still officially on the run, McKearney made no secret of his mindset: if confronted by British forces, he would fight his way out—or die trying.

The team then began equipping themselves with their weapons. The arsenal reportedly included three Heckler & Koch G3 rifles, two FN FNC assault rifles, one FN FAL battle rifle, and a Franchi SPAS-12 combat shotgun. The SPAS-12, an Italian-made, military-grade weapon, was notable for its dual-mode operation, capable of switching between semi-automatic and pump-action firing. Designed for close-quarters combat, it was rare in the conflict and underscored the unit’s escalating firepower and tactical preparation.Padraig McKearney carried the .357 Ruger revolver taken from the raid on Ballygawley station in December 1985.

At approximately 7:20 p.m., the East Tyrone Brigade’s Active Service Unit began what they believed would be a swift and decisive strike.

Declan Arthurs led the assault, driving the digger toward the village with its front bucket raised high, carrying a 200 kg bomb packed beneath bricks and rubble. The machine moved slowly, its front wheels jolting under the weight of the device.

The IRA convoy approached Loughgall from two directions. The digger, driven by Declan Arthurs, came in from the Portadown side, while the Toyota HiAce van carrying the remaining seven Volunteers approached from the Armagh direction, converging on a road that merged near the village. According to accounts, the van had been delayed, with the digger and scout cars waiting for its arrival.

Declan Arthurs, known within the unit for being security-conscious and tactically cautious, took the lead in a preliminary scouting run. Driving the hijacked digger, he passed through Loughgall village, slowing as he approached the RUC station to observe its exterior and immediate surroundings. After passing the target, he pulled the digger into a nearby lane, where he made contact with the van team. Arthurs then turned the machine around and passed the station a second time.

The van then performed the same manoeuvre. At some point, doubt must have crept in—whether due to unease, timing, or subtle signs. One of the Volunteers returned in a scout car for a final sweep of the area.

The operation involved four vehicles in total: the JCB digger, a blue Toyota HiAce van, and two scout cars—with at least three IRA Volunteers reportedly assigned to scouting roles, providing cover and intelligence for the primary assault team.

The streets were silent, the station appeared empty, and the village unnaturally still.

The plan was simple and had worked before: ram the digger through the station’s pathetic wire-mesh perimeter, set the 40-second fuse, and withdraw to the waiting van parked slightly ahead, its rear door flung open. Once all three were aboard, the van would speed away under covering fire from the rest of the team.

Unbeknownst to the IRA unit, they had passed within mere feet of covert SAS operatives—faces blackened, weapons ready, and positions concealed days in advance. The soldiers held their fire through this initial phase, allowing the operation to unfold. Although they could have engaged earlier, the decision was made to permit the IRA to initiate the attack, thereby framing the subsequent use of lethal force as reactive. The IRA volunteers would be permitted to bomb the station, possibly even destroy it—only then would the trap be sprung.

With Paddy Kelly giving the order to begin the attack, Gerard O’Callaghan and Tony Gormley hopped out of the van and into the digger with Declan Arthurs.

Arthurs then set the digger in motion, driving past the RUC station once more, with the van following closely behind. The convoy moved steadily through the quiet village, heading toward the seemingly inactive police base. According to witness testimony at the1995 inquest, the vehicles were moving so slowly that “a policeman could have stood out in front of it”—a detail later cited by critics as evidence that no attempt was made to arrest the team before the ambush was sprung.

As the two vehicles approached the target, the digger paused briefly and the HiAce van pulled up alongside it. After a short exchange between the crews, Declan Arthurs swung the digger sharply to the right, crashing through the perimeter gate and breaching the station’s outer defences.

The JCB digger used at Loughgall was lighter and less powerful than the machine previously deployed at The Birches, and the Loughgall RUC station itself was more heavily fortified. A combination of a low perimeter wall and a reinforced security fence prevented a full breach—leaving the digger partially through the wall, but still mostly positioned outside the compound’s boundary.

The three IRA Volunteers jumped from the digger just as the van team—carrying the other five men—arrived on the scene. The van came to a halt further up the road, positioned on the opposite side of the station to provide cover and overwatch.

Arthurs and Gormley, each holding a cigarette lighter, clambered through the wreckage of the breached fence toward the bucket of the digger, which carried a 200 kg explosive device. Reaching the bomb, they lit the two forty-second fuses, initiating the final stage of the attack.

Exactly what happened next remains disputed, but one account comes from former RUC Special Branch officer John Shackles, who described how the SAS had rigged detonating cord along a line of fir trees beyond a playing field opposite the station. Just seconds before the ambush was launched, the cord was detonated, producing a sudden blast designed to distract and disorient the IRA team. As the Volunteers instinctively turned toward the explosion, SAS operatives inside the station opened fire, launching the ambush under the cover of confusion.

The Toyota van, which had pulled up near the station, was immediately raked with sustained and rapid gunfire from the station’s first-floor windows. According to Fr Raymond Murray, a human rights campaigner and author, only Seamus Donnelly managed to exit the vehicle. He attempted to flee toward the football field opposite the barracks by jumping over a locked gate. Donnelly was gunned down just ten yards into the field by waiting SAS troopers.

Gerard O’Callaghan and Tony Gormley, who had jumped from the digger alongside Declan Arthurs, were caught in a devastating crossfire—simultaneously hit from both front and rear as they tried to reach the waiting van. Gormley, unarmed at the time, was carrying only a Zippo lighter, used moments earlier to ignite one of the bomb’s two fuses. O’Callaghan and Gormley were shot dead around 20 yards away from each other.

At the same time, the Toyota van was being subjected sustained machine gun fire—from the side by the “kill team” inside the station compound, and from the front by one of the “cut-off” units. Pinned down in a lethal crossfire with no room to manoeuvre, the IRA men inside never stood a chance.

Declan Arthurs managed to run approximately 80 yards up the road, heading away from the station and in the direction of Portadown, before he was struck and killed by gunfire. His body was later found face-down on the roadside, separated from the others, suggesting he had made a desperate attempt to escape the kill zone.

Hundreds of rounds—with some reports suggesting over 1,200—were fired at the IRA unit during the ambush. According to a later account published in Big Boys’ Rules, one SAS trooper “tap-danced” as he fired a GPMG into the van—a grim detail that underscored the brutal determination behind the British ambush.

With most of the 24-man SAS ambush team firing directly into the kill zone, the digger bomb detonated, obliterating one side of the RUC station and scattering debris across a wide area. In the aftermath, both wheels of the digger could be seen in post-incident photographs—one of them having smashed through the fence opposite the station and come to rest in the playing field.

Just as the bomb in the digger bucket detonated, a white Citroën (registration: OIA 3428) carrying two brothers—Anthony and Oliver Hughes—was making its way through Loughgall village. The pair had spent the day repairing a lorry driveshaft at a friend’s farm and were on their way home. Unaware of the ambush unfolding ahead, they took what seemed to be the more direct route through the village.

As their car crested the hill near the church, the brothers spotted smoke rising from the police station and briefly considered turning back. Before they could act, SAS troopers, concealed in a nearby residential garden, opened fire. The car was riddled with bullets: the front windscreen, which faced toward the IRA’s approach, remained intact, while the rear and side windows were shattered. The passenger side, where Oliver was seated, sustained seventeen bullet holes.

Anthony Hughes was killed instantly. Oliver was severely wounded, suffering gunshot wounds to the right side of his back, left shoulder, and left temple; his lungs collapsed from the trauma. He later stated that no crossfire occurred near the car, directly contradicting the official RUC account. In his view, the brothers were mistaken for IRA Volunteers, partly because they were wearing blue overalls, similar to the IRA unit’s boiler suits.

Despite the clear evidence of mistaken identity, the RUC refused to publicly acknowledge that the Hughes brothers were civilians.

Meanwhile, just 250 yards away, a parents' meeting of the Loughgall Girls’ Friendly Society was taking place at St Luke’s parish hall. The blast and subsequent gunfire shattered windows in the hall, but heavy curtains spared those inside from injury.

Just outside St Luke’s parish hall, Mrs Beggs, a local woman, was driving into the village in her red Mazda when the shooting began. As she crested the hill, three bullets struck her car from behind. Miraculously, she escaped unhurt.

A short distance away, three members of the Loughgall Football Club committee, who had been preparing to open their wooden clubhouse bar, suddenly found themselves under fire. When the shooting erupted, they threw themselves to the ground. Moments later, the digger bomb detonated, sending shards of glass and masonry raining down on them. All three survived.

Victor Halligan, one of the men inside, later gave an account to Fr Raymond Murray, recorded in The SAS in Ireland. “The next thing we knew was that soldiers burst in and took us outside,” he said. “At one stage I got the impression they thought we may have been involved, as they had their guns trained on us.” The men were forced to sit on a wall outside the clubhouse, not permitted to look toward the station, and were separated and held for several hours. Eventually, a local RUC officer identified them, and they were allowed to return home. Halligan remembered the moment vividly: “As we walked home we saw two bodies, one lying against a wall [Declan Arthurs] and one lying beside a white car [one of the Hughes brothers].”

Another civilian—a man in his forties from Maghery—was also caught up in the ambush. Driving into Loughgall from the Armagh side, in the opposite direction from the IRA unit, he was en route to a football match when the gunfire erupted. Just 25 yards from the IRA van, he jumped from his car and took cover between two gable walls. “I lay there flat on the ground for what seemed like an eternity, praying to God for myself and my family,” he later told Fr Murray.

When the firing stopped, he was arrested where he lay by soldiers with blackened faces and English accents, and taken to Gough Interrogation Centre, where he was held for five hours. His family were unaware of his whereabouts until he called from Gough Barracks in the early hours of Saturday morning. Later treated by a doctor for severe nervous shock, he told The Democrat newspaper: “If I had driven another twenty yards, I’m sure I would be a dead man. I ran from the car when I heard the shooting; the explosion came later as I lay on the ground.”

According to the Sunday Tribune (10 May 1987), three local boys who arrived at the scene shortly after the ambush reported encountering at least three armed men in military uniforms, wearing balaclavas and speaking with English accents. The boys said British soldiers told them they had chased one IRA man up the road toward Portadown—believed to be the body later found furthest from the RUC station.

Soldiers were reported firing from multiple locations: the Armagh side of the village at the IRA van; the football field opposite the barracks, where Seamus Donnelly was likely shot; and a garden on the village side, from which Anthony and Oliver Hughes were mistakenly gunned down. Every exit from Loughgall appeared to be sealed, and it was clear that the operation had been designed as a contain-and-kill ambush.

In the course of the entire operation, two RUC officers and one British soldier were slightly injured by shrapnel. No British casualties were caused by enemy fire.

Meanwhile, two IRA scouts who’d been waiting a short distance outside of the village, sat and waited as the sound of gunfire battered the air. According to an account given in May 2017 to The Irish News on the 30th anniversary of the ambush, the gunfire “went on and on, for what seemed like three to four minutes”. One of the scouts became concerned:

“Out in the distance I saw a helicopter and I turned to [a comrade] and said ‘there’s something badly wrong here’.

“At this stage we were waiting for them (the IRA team) to come down and get away.”

He recalled seeing several SAS soldiers leap from behind a wall and rush toward the Hiace van, which lay just ahead. One SAS man stood just two or three feet in front of the Volunteer’s vehicle and levelled an M16 Armalite rifle at his chest.

“I know for a fact to this day, when you look in someone’s eyes, they knew we were involved. They had observed us for 20 minutes before it.”

Frozen in place, the Volunteer could see the van and the bodies of his comrades lying around it.

“The SAS men with us were calm, but the boys around the van were in a frenzy. At that stage there was an odd isolated shot… I knew they were wiped out. I could see the carnage down at the van. At the same time, it was a shock to know everybody was away.”